Michael Sumerton’s Heartwarming Journey: Doing it Right

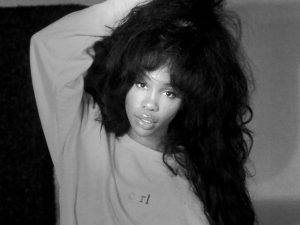

Sumerton’s family celebrates his successful open heart surgery. In Sumerton’s arms is the pillow depicting the process of the Ross procedure, where the malfunctioning aortic valve is replaced by the pulmonary one.

February 2, 2021

Michael Sumerton’s family doctor listened carefully through his stethoscope and heard something he didn’t like — a subtle murmur, like the whoosh and swish of leaves rustling in a soft wind. The doctor removed his stethoscope and his half rimless minot glasses and told Sumerton, “You need to see a cardiologist. Immediately.”

That was four years ago. The assistant principal found out he had bicuspid valve disease, a hereditary disorder. Instead of having the usual three leaflets in his aortic valve, he only had two, which left a small hole — a leak — in that valve. Though there are few symptoms other than the tell-tale murmur, the disorder often leads to calcium building up on the misshaped leaflets, encrusting the valve so it resembles a rusty valve. Sumerton’s aortic valve was caked so badly it could barely open and shut.

Just over two weeks after the initial diagnosis, Dr. Cyril Ruwende, the cardiologist, sat a few feet apart from Sumerton in a small white room with a puke-green bed.

“Look, I don’t need to live forever,” Sumerton said. “I just want to live long enough to raise my kids.”

The average size of an aortic artery is approximately 3.5 centimeters. At 4.5 centimeters, there is a risk of heart rupture. Sumerton’s aortic artery was at 3.9 centimeters and growing.

“How old are your kids?” Dr. Ruwende asked.

“17, 15, 14, 12, 8—” Sumerton started.

Dr. Ruwende interrupted him.

“Wait. There’s more,” Sumerton added. In fact, five more. Mr. Sumerton and his wife have 10 children.

“I think you’ll be able to make this happen,” Dr. Ruwende said.

Think?

“Think” meant there was a chance he wouldn’t live enough years to be the dad he wanted to be. In other words, “Think” was unthinkable.

“That was emotionally the hardest moment,” Sumerton said. “I thought, ‘I have responsibilities to my kids and to students, and I may not be able to fulfill what I promised people.’”

In 2020 he was given less than a year to live.

“Man, I’m on the short end of this, not the long end,” Sumerton told himself. “Things are happening all over the world. Good things. Bad things. They’re happening. That story keeps going, and I’m just out of it — like I was never here.”

He realized that waking up tomorrow is a gift not to be wasted.

“It really hit me that I have a short window to do as much good as I can before I’m gone,” Sumerton said.

So, every day started to become more precious.

“One more day to do it right” became his mantra. Through prayer and hours of research about his treatment options, it all became clear. He realized this was an opportunity to do something special, but he had to act quickly. In 1966, Sumerton’s grandfather had died at the age of 56 of a heart attack caused by bicuspid valve disease.

One year later, a South African-born British thoracic surgeon, Donald Ross, discovered a way to replace a patient’s damaged aortic valve with their own pulmonary valve. The procedure — called the Ross Procedure — has saved the lives of countless people, and one of the most accomplished surgeons in this field, Dr. Andrew Pruitt, operates out of Saint Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ypsilanti, Michigan, right in Sumerton’s backyard.

“It’s like I’m walking down a stream, not knowing if I can make it,” Sumerton said. “Then, I look down, and there are rocks perfectly placed for me to walk across. Every question, every problem I had was always solved.”

Usually, Dr. Pruitt’s surgery schedule was booked for months ahead, but when Sumerton approached him, the doctor found an open spot 10 days later.

Before the Nov. 2 surgery, the Sumerton family met around their 12 by 3 foot maple wood table to discuss over dinner the surgery and what to expect. His four-year-old son, Peter, raised his little hand.

“Dad, are we still going to be able to wrestle?” he asked.

“Yes, but not right away,” Sumerton told him.

That was all Peter needed to know, as he happily began to munch on his spaghetti.

“My dad is a great father,” Sumerton’s son Max, 12, said. “He’s the one who makes everything fun at home. He provides for us and protects us. He is my dad, but he’s also one of my best friends.”

Another one of Sumerton’s best friends, whom he has known for a decade, is Huron High School College Prep advisory and business teacher Christine Garrett.

“He is loving and just the most giving person you will ever meet,” Garrett said. “Everything comes from a good place — such a real place of trying to understand who people are and how to help people. And that’s just at his core. What he cares about is elevating them and making them better.”

As the big day rapidly approached, Sumerton’s community was now the one elevating him. The PTSO sent him $350 worth of gift cards. Parents, teachers, students and friends signed up to bring meals to his family 60 days in a row. Seventy families signed up to pray for him non-stop during and after the operation.

“I really was totally blown away by all of these actions,” Sumerton said. “There’s just been an incredible amount of support, and it has made it really easy to go through the surgery.”

The success rate for the Ross procedure is 96 percent, and Dr. Pruitt’s success rate is over 99 percent. However, there was still a chance for the worst, and Sumerton was at peace with that possibility.

“If I go because of this, don’t be upset,” Sumerton told his loved ones. “If this is my time to go, then it is. If not, then obviously God has more for me to do.”

As the nurses sedated Sumerton, they asked him what kind of music he wanted to listen to. He doesn’t remember his response.

Eight hours later, the surgery was over. Sumerton woke up.

“Hey, did I pick the music yet?” he asked.

He had some bluegrass tunes in mind.

“When I woke up, I felt like I had almost died, then came back to life,” Sumerton said. “It’s really, really strange, just how different it feels to have a fully functioning heart. It’s a night-and-day difference.”

Within the first hours with his new “Marvel superhero heart,” Sumerton posted on his Facebook a fascinating picture of his chest opened by metal clamps and a clot of tubes dangling out. The next day, the post was blurred and flagged with a graphic warning.

“This is so weird to say, but I have had a really awesome experience and this surgery has been one of the coolest things I’ve ever gotten to do,” Sumerton said. “It’s something not many people get to do, and I feel like I’m lucky to have had this experience.”

His recovery is going smoothly, and he can now go up a flight of stairs without exertion. Sumerton said he plans to run a half marathon soon and is already signed up for a 10K run in the summer. Best of all, he may even be able to go back to work sooner than expected, a possibility that thrills him.

“It was me dragging my heart along for 47 years and now my heart’s like ‘Hey, let’s go!’” he said. “I feel like I’ve been brought back for a reason. And I’m excited to get started.”

Michelle Machiele • Mar 23, 2021 at 9:08 am

Wonderful article, Allison. Inspiring!