Lessons from a Japanese internment camp survivor: Mary Kamidoi

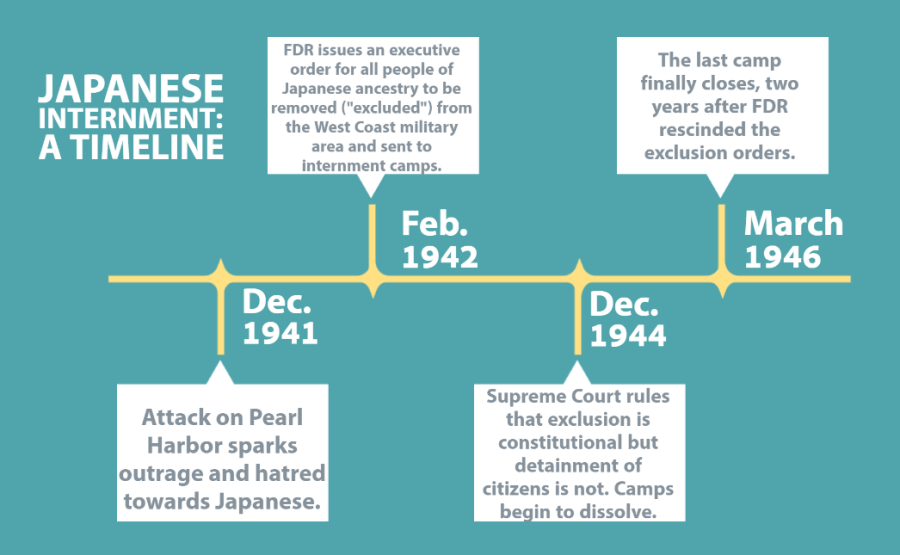

A timeline of Japanese internment after the Pearl Harbor attacks during World War II.

May 23, 2023

Over 80 years out from the moment she stepped in, Mary Kamidoi can still draw a picture of the internment camp from memory. And she’s determined to keep that memory alive.

“That’s the impression that it left with me,” Kamidoi said. “I probably will never forget that lifestyle.”

Kamidoi was only 11 years old when the U.S. government forced her and her family to take all they could carry and move to a Japanese internment camp.

“So what does an 11-year-old kid carry?” she said at “Lessons for the Future, Lessons from the Past” at the Ann Arbor District Library on Monday, May 15. “My toys, probably, and my dolls. My mother would say, ‘what are you going to do for clothes?’ I said, ‘yeah, but I can’t leave my toys.’”

Kamidoi and her family were just a few of the 127,000 Japanese-Americans placed in internment camps by the government for the duration of World War II. They were forced to live in relative isolation from the rest of the world and perform labor for the government, under the pretense of national security after the Pearl Harbor attacks. Now, it’s a part of history most people prefer to forget. Some second- and third-generation descendants of internees barely even know it happened.

“They even tell you, ‘I didn’t know, my parents never told us about it,’” Kamidoi said. “I said, I’ll tell you why your parents never told you. Our parents were so ashamed of the fact that they could not protect their kids when we were being shoved into camps.”

Kamidoi herself does not have children, but she is intent on retelling her experiences to her nieces and nephews — not just about the camp conditions, but the slow climb back into society after the camps closed.

“My sisters never told their children the true story,” Kamidoi said. “And so I would sit them down and I’d tell them what happened. Actually among the people that lived in these camps and lived that life, they don’t talk about it, because it was such a struggle, especially getting out of camp and trying to start life.”

In Detroit, where her family moved after the camps closed, Kamidoi says guilt is a big motivator for parents not explaining their history to their children. Many of them lived in close quarters in cheap apartments, with two or three families sharing the same space to save money.

“They don’t want to worry them and make them feel guilty for what they have,” Kamidoi said. “But I said the kids should know some of this, because life isn’t going to be that easy for them. Not all the kids are going to be able to live high on the hog and live in nice houses and have nice cars. They’re going to have to be suffering every now and then, so you need to tell them what suffering is all about.”

Kamidoi’s activism and determination to make change blossomed when she was still in school, determined to end the bullying she and her sister faced. Two boys on the bus would throw paper airplanes at her, white sheets with red circles to mimic the Japanese flag — so she went to their parents’ house and demanded they tell their children to stop, even threatening to tell their landlord to evict them.

“I said to them, tomorrow, if there’s one plane, you won’t be living next door to me,” Kamidoi said, recalling the teenage girl she once was, standing at a stranger’s door. “I said, today, I’m giving you a second chance.”

The landlord had advised her to go to him if she had any problems with anyone in town — and Kamidoi quickly learned that making connections in high places was her smartest path to make change. She walked right into the office of the general manager of her job at Ford, and within minutes, he was writing a memo to every employee to treat her and her sister better.

“I looked around and I thought, none of you guys have the nerve to come in here,” Kamidoi said. “I have the nerve. And my nerve will go further than this if I have to.”

Racism in the workplace affected many of Kamidoi’s Japanese friends as well, but she says their culture was a barrier to speaking up.

“Our culture is to be nice, speak softly, don’t be nasty to people, and to put up with anything that you’re not happy about,” Kamidoi said. “The word “gaman” was always thrown at us kids, and that means to put up with people.”

“Gaman” is a term often associated specifically with the Japanese internment camp survivors. It means “enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity,” but was often interpreted as a lack of assertiveness. Kamidoi was tired of putting up with people, despite the backlash from her own family.

“I used to go home and visit my mother, and tell her what was happening, and she was always upset with me- ‘what did I teach you?’” Kamidoi said. “I said yeah, you taught me that word, but you can only put up with nastiness for so long. You work with these people day in and day out. You’re sitting in the same office and they don’t speak to you, they don’t ask you if you want to go on break, if you want to go to lunch — so I said, I don’t want to hear that word anymore.”

Today, Kamidoi hopes to spread her lifelong confidence and passion for activism to everyone around her, especially those who have been taught to practice tolerance instead.

“All of you,” she said, 93 years old now, looking out at the crowd, “You have the same rights as the next person. Don’t let anybody keep stomping on you. Forget that word [“gaman”], times are different now. Start telling them exactly how you feel, and let them know that you’re really getting upset over this treatment. There’s no reason for them to mistreat us.”