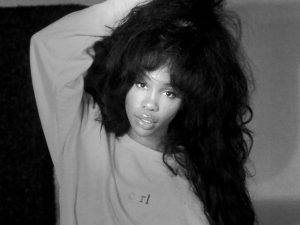

‘It’s just like falling in love’: Soyeon Kim’s journey to adopting her son

For Huron art teacher, Soyeon Kim, the process of adopting her son was difficult and lengthy. However, it was worth it in the end. “He brings so much joy to our family,” Kim said.

February 1, 2022

Soyeon Kim says it’s just like falling in love. Her dream since what-feels-like-forever, that is. Her dream of adopting a child.

“Sometimes you romanticize something for so long you can’t remember when it all started,” Huron art teacher Kim said. “Over the years, the idea just got bigger and bigger.”

And bigger. And bigger. Until it was real.

“Parenting is the most noble thing I can do while I’m living,” said Kim, who started the adoption process in October of 2018.

After completing their adoption application, Kim and her husband expected to meet their child within six months. But it would be three arduous years until they finally would.

The first obstacle arose the day after they submitted their application, when the agency they were planning on working with suddenly closed down, “just disappeared.” It took two more months for Kim and her husband to find a complementary agency: one located 520 miles from home, in Washington, DC.

From there, it only got more challenging.

In addition to the $50,000 cost, the adoption process entailed mounds of fine-tooth-combed paperwork, 50 one-hour classes, and at least one 500-question exam. Kim even had to write a letter to the biological mother, without knowing who that would be or if the baby had yet been conceived.

Every minute detail mattered. In one instance, Kim’s failure to check off one of 200 some boxes immediately eliminated her from matching with a baby. Based on a multiple-choice assessment, Kim’s doctor noted her as “[mildly] stressed,” and one sentence from the sea of paragraphs she wrote was deemed by the agency to be a “problem.”

“It was just very discouraging,” Kim said. “I already had to pay a lot of money and had a nursing room all set up. I was already financially, physically and emotionally invested.”

But for over two years, Kim had to play the waiting game.

“It was pushback, pushback, pushback,” Kim said. “It was heartbreaking. Like, I have to wait longer? Is this ever really going to happen?”

Though the sporadic feelings of discouragement would linger for a few days, Kim always kept her chin up and saw a benefit to these delays.

“A little bit more time was given to me to do my stuff,” Kim said. “So, I chose to enjoy every piece of it.”

For Kim, this meant drawing whenever she could.

“I’ve never drawn that much, except for college,” said Kim, a graduate of the University of Michigan School of Art and Design.

Some days, she drew for three to five hours, while on busy days, for just a few minutes, but Kim kept it consistent. She drew for herself, but also for commissioned artwork, which helped offset adoption costs.

In February, 2021, it finally happened. Kim matched with a baby. An 8-month old boy in Korea, with almond-shaped eyes and rounded cheeks. Over a virtual meeting, Kim and her husband met with an agency representative. The child’s files were shared, along with “aw”-inducing videos of him “wobbling” in his crib and pictures of his 100-day milestone.

“When I saw the photos, I screamed,” Kim said. “It was a moment. It was the moment.”

Before Kim and her husband departed for Korea to pick up their son, they had one more very important task: naming their child.

With a teeming list of name recommendations from family members in hand, Kim sat down at her easel and started drawing her son, referring to the agency’s pictures. As she sketched his eyebrows, she started trying to match names. Arbor. Leo. Bentley. Austin. Liam.

“Liam,” Kim thought. “That’s perfect.”

Shortly afterwards, a customized grey fuzzy blanket, which read, “Let’s Go Liam!” was shipped to the Kim household.

Upon arrival in Korea, Kim and her husband quarantined for two weeks, then were finally able to meet Liam.

It didn’t feel real. They had pored over pictures, videos, her own pencil sketches of Liam. And suddenly, there he was, ten feet away, jauntily dressed in a denim jumper overlapping a white undershirt.

“It felt surreal,” Kim said.

And then he voluntarily approached Kim and sat on her lap, beginning to curiously play with her pearl necklace.

“We were all so shocked,” Kim said. “The foster mom was really shocked, because he was usually shy, acted invisible to strangers and had frequent tantrums.”

After visiting Liam three times over the course of four more weeks, it was time to bring him home. Some worries began to simmer for Kim.

“What if I’m a bad parent?” Kim worried. “What if there’s a foreign feeling that lingers too long?”

The fact that this was her first child made it even more difficult.

“In our hotel, he was opening all the possible doors, pressing all the buttons and bumping into all the furniture,” Kim said.

Liam’s amounting bruises from his adventurous behavior caused Kim to panic.

“Don’t worry,” another parent told her, alleviating Kim’s worries. “Kids do that all the time.”

On the flight to America, Kim still couldn’t believe that the boy in the blue and yellow-striped pants and baby blue shirt sleeping on her husband’s chest was her son.

“Is it real?” Kim continuously thought. “Is he really mine?”

For the first few weeks back home, Kim described the feeling as babysitting someone else’s child.

“I love this boy,” Kim said, “but it still doesn’t feel like he’s my son.”

She thought that this uncomfortable feeling arose because Liam was adopted. However, when Kim talked to more parents, she found that even parents who had given birth to their children felt exactly the same.

Two weeks later, it started to get better.

“It started to get really real,” Kim said. “Getting a child, whether it’s by adoption or birth, is like a blind date, and then you get married, and you’re committed. Of course if you really like the person you go out on a blind date with, you have excitement. But you still don’t see him as your husband immediately. Meeting Liam was the same.”

By the seven-week mark, everything fell into place.

“He’s just my child,” Kim said. “And that’s the core of parenting. It’s not so much about our DNA sharing. It’s the relationship we get to build together.”

When parents would shed tears as they dropped their children off to daycare, Kim used to watch in confusion.

“What’s the big deal?” she would think.

However, when it was her turn to drop off Liam, it was very emotional.

“Whatever steps he’s going through, I feel like I’m emotionally attached,” Kim said. “And my husband feels the same way. Us going through the process together has made us tighter.”

According to Kim, the three of them — Kim, her husband, and Liam — are a team.

“It’s really powerful,” Kim said.

And best of all, Kim still has time to draw.

“Because I drew so fervently for two years, it became second nature for me to draw fast,” Kim said. “I expected I wouldn’t have time, but practice really didn’t fail me.”

Kim is so happy with Liam that she is even considering a second child.

“The process was very difficult, but it was so worth doing,” said Kim, who uses nine gigabytes a month on pictures of Liam. “He brings so much joy to our family.”

Kim’s personal favorite memories of Liam are when he babbles his “alien language” consisting of pouts and “wows,” defensively clings to his cobalt blue toothbrush, or when, as he sleds down the snowy sidewalks, tailed by their Yorkshire Terrier, Cookie, he never fails to wave.

“I forget what my life was like without Liam,” Kim said. “It feels like he’s been here forever. And it really is just like falling in love.”

Nancy Clark • Oct 14, 2022 at 4:14 pm

I am blown away by the written words. Thank you .