‘You just have to keep going’: The heartaches of nurses during the pandemic

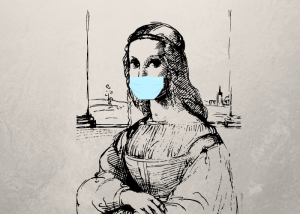

Lanie Burns, who was deployed to the COVID floor for 6 weeks last spring, dresses in full PPE.

April 23, 2021

“I think I cried most nights,” I.C.U. nurse Lanie Burns admitted, recalling last spring when she was deployed to the COVID floor. “Especially in the beginning, it really did feel like things were falling apart for a while. It really did feel like we were at war.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck Michigan last April, the University of Michigan medical center was mainly missing two things: N95 masks and I.C.U.-trained nurses.

It typically takes 15 weeks for a nurse to become I.C.U. trained, but to feel completely proficient, according to Burns, it takes up to a year. However, due to the shortage of I.C.U. nurses during the COVID-19 surge, many regular nurses had to be trained on the spot. Unpressured practice was tossed out the window for them.

“You throw these nurses into this situation where it’s a crisis and they’ve never seen a ventilator before, they’ve never had to titrate sedation, and you basically give them no training and say ‘Hey, just try and keep them alive,’” Burns said.

Or as nurse practitioner Raymond Blush commented, “It’s like we’re flying the airplane while we’re building it.”

Amongst a team of four to five regulars, Burns was the only I.C.U- trained nurse and had to lead them. She feels very lucky that even though the nurses with her were not I.C.U.-trained, they had had prior experience with severely sick patients. However, she knows some of her co-workers had much more trouble leading less-experienced nurses while treating patients.

“You can have the best nurse helping you, but it’s still really overwhelming to have four patients that are bad sick and only one I.C.U.-trained nurse,” Burns observed.

Last spring, another scarcity in the hospital was protective gear: eyeshields, bouffants, plastic gowns, shoe covers and most important of all, N95 masks.

“You just treated your N95 like gold and tried to make it last as long as possible,” Burns said.

Her personal time record? Two weeks, which was an average amongst her coworkers.

Currently, such resources for nurses are much more abundant, though Powered Air Purifying Respirators (PAPR), which supplant the more problematic masks, have recently been deemed the new, rare commodity.

During those six weeks when Burns was on the COVID-19 floor, due to the large number of patients, she was working at least four to five days a week, each day a 12-hour shift.

“A lot of us who are working literally put our lives on hold to take care of these patients,” Burns said.

She knows nurses who stayed in hotels instead of living with their children and spouses in fear of transmitting the virus.

For Natalie Elliot, who was formerly in an adult medical progressive care unit and is now in a COVID-19 I.C.U., it was her first Christmas without her family. They decided it was best if she did not visit them that year to avoid possible infection of the virus.

“It was sad,” Elliot said, “sitting at home with only one other person. I’m glad I wasn’t all by myself, but it was definitely sad.”

As well as the physical exertion demanded to help each patient, emotionally, it has been as challenging.

For most nurses on the I.C.U. floor, witnessing deaths is merely part of the job.

“There are definitely many deaths that happen quickly,” Elliot said. “It’s really sad, but you have other patients to take care of, too.”

She paused for a moment.

“So you just have to keep going.”

In fact, a recent survey for nurses found that 50% of its respondents experienced signs of depression and anxiety, while almost one-third had symptoms of PTSD.

“I think many of us carry a lot of what we saw and what we experienced with us still and we just really hope that we never have to see it get that bad again,” Burns said.

And for Elliot, who is still on the COVID battlefield, the emotional weight is still ever present. The most difficult time, she notes, is when she has to hold the phone up when a patient’s family is FaceTiming them, and the patient is lying in bed, sedated and supported by a breathing machine.

“Just hearing the family talk through the phone, I can’t imagine what that would be like, to not be able to come and see your loved one,” she said.

Elliot vividly recalls one patient whose partner dropped off a cassette tape and a cassette player at the hospital. The cassette, set on the bedside table of the sedate patient, played his favorite songs and in-between each song was a recorded message from his wife. Sometimes it was “I love you” and others it was “Keep fighting.”

When the patient woke up, Elliot told him she enjoyed the songs from the tape.

“Do you remember your wife talking to you?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said. “I remember.”

The patient got better and was afterward able to be moved to a step-down unit.

Symptoms for COVID-19 can be as innocuous as a cough for some. But for many others, it can be as lethal as not being able to breathe on their own, and every day, nurses still show up to help those people.

“I was putting in really long hours and I was turning on the news and seeing people who were protesting in Lansing and people who weren’t wearing masks,” Burns said. “I felt like if people don’t take this seriously, I’m going to be doing this forever. And I can barely do this right now.”