Lessons from pizza

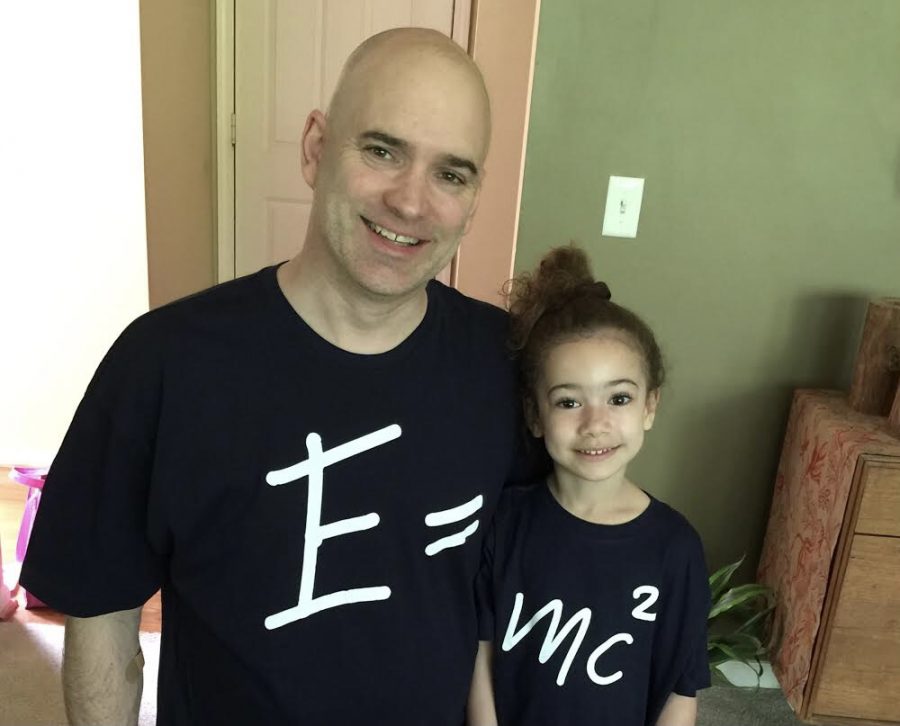

This is the day Wheeler adopted his daughter, Jasmine, back in 2016.

April 22, 2021

Part 1

Stephen Wheeler ashamedly admits that his most traumatic moment occurred at the ripe old age of 19 when he had to make himself a bologna sandwich for dinner. In his mind, there was no other more rational response since he, a fervent anti-vegetablist, saw that the other meal option was a plate of imposing stuffed green peppers from his mother’s hours of kitchen handiwork.

“Oh good Lord, how freaking entitled I was,” Wheeler reflected. “I just had to be a little snot and make a sandwich.”

Wheeler went on to talk about his privileged childhood.

“I grew up in an affluent family in the bubble of the University of Michigan. Everything was just a little ivory tower world,” Wheeler said.

He further explains that his only exposure to homelessness was through Shakey Jake, a famous homeless man who often wandered downtown Ann Arbor with songs and stories while he panhandled. Through Wheeler’s eyes, Jake was the typical homeless person: famous and the only one per city.

“Then, I stepped out into the real world and went, ‘Wow, this is really different,’” he said.

Wheeler was 15 one of the first times he stepped out of the bubble. During a spring break vacation in San Francisco, his misconception of homeless people was quickly debunked at the sight of myriads of homeless people holding signs that read, “I have AIDS. Please help.”

“My sister smacked me and said, ‘Stop staring at the homeless people,’” Wheeler said. “And it wasn’t that I intended to do that. I had just never seen anything like that. All these stories that I heard on the news, they never really conveyed how bleak it felt.”

Wheeler noted how contrasting his father’s upbringing was a stark contrast to his own. When his dad was a teenager, in fact, he was employed digging trenches along the side of the road. He later went into the army and the Marine Corps, attended university on the GI Bill and became an accounting professor at the University of Michigan.

“My dad knew what need was,” Wheeler said. “I didn’t know what need was. I didn’t really know anybody that knew what need was either. I knew people who went without certain extras, but I didn’t know people who struggled every single day.”

Part 2

In July 1993, in Portland, Oregon, Wheeler, having just graduated from college, was walking with two pepperoni pizza slices in hand, freshly purchased from Escape From New York Pizza. He was almost 2,000 miles away from home in a new city, feeling blue and lonely. But he wasn’t the only one.

A homeless man slumped against a wall asked Wheeler despondently for spare change as he walked by.

“The thing that struck me about it was that he wasn’t trying to put on a show,” Wheeler said. “He just felt sad, and I was sad at that moment, too. I thought, ‘This is somebody that I have something in common with.’”

Wheeler didn’t have any cash since he had spent it on the pizza. So, he offered his second slice.

“He had a moment of joy and that really touched me,” Wheeler said. “His reaction in turn lifted my mood so much.”

Over the next three months, the couple of times a week Wheeler bought pizza, he would make sure to purchase one for the homeless man — his new friend.

They would sit on the stairs by the pizza place, eat and talk about Robert Jordan novels.

“[This whole encounter] opened my eyes to how fortunate I had been,” Wheeler said. “And I really didn’t do anything to earn being in that position. It was just a stroke of luck, and there’s nothing that prevents me from no longer being in my position at a later date.”

Part 3

“I think your purpose changes throughout life,” Wheeler said, leaning back and waxing philosophical.

After he majored in business as an undergraduate, he worked as a customer service manager at an Oregon pager company, and on the side, as a high school volleyball coach — the job that realigned his purpose.

“It was such a fulfilling experience,” Wheeler said. “I thought to myself, ‘It’s crazy, I spend my days at work thinking about volleyball practice, rather than focusing or enjoying my work. I need to make that more of a full time gig rather than just a couple hours a day.’”

So, he went back to school at Eastern Michigan University to obtain his English and math degrees, which inevitably led him to teaching.

“I stayed with teaching because I love kids,” he said. “I love the variety of people that I get to work with. I love that you get to share so many experiences with students and experience so much growth with them. I don’t think there’s another career that would have that same opportunity.”

Prior to coming to Huron, Wheeler worked at Romulus High School for 16 years. While there, he took part in a dropout prevention program for kids who had gotten in trouble at the regular high school or those who had legal troubles outside of school.

“We had a lot of gang kids, kids from rough backgrounds and many unmotivated kids who just didn’t see where education was going to get them,” Wheeler said.

One of the students, who was part of this program, encountered Wheeler in Meijers a few years after he graduated from that program.

“The student told me how he went to community college and then got into Madonna Nursing School,” Wheeler said. “He was just so excited and so appreciative of everything: the teachers and the program. It was just a very exciting moment. If I’m feeling down or frustrated about something, I reflect back on that and I’m like, ‘Okay, we can get this done because this is the potential end result.’”

Wheeler came to Huron through Philip Eliason, the former precalculus teacher, who was Wheeler’s eldest sister’s best man. Eliason reached out in the end of 2019 to see if Wheeler would be interested in a teaching position. Wheeler started at Huron in Jan., 2020 teaching geometry. Even though he only spent a short period of time in-person at Huron, Wheeler has already felt incredibly connected to the math department.

“I don’t think I could say enough positive things about it,” he said. “They’re really amazing. It’s such a close-knit group and we’re all there for each other. It really just felt like being adopted into a family.”

Wheeler currently teaches the precalculus classes. Nevertheless, no matter which level of math he’s teaching, seeing the joy, the twinkle in the eyes and the “Aha!” moment in students as they master a subject, is one of the main reasons he got into this profession.

But at the end of the day, for Wheeler, no matter whether he is facing a geometry student or a homeless person, it comes down to kindness and its humble, unexplainable reward.

“You know that you contributed to that person’s life in some way that’s positive,” Wheeler said. “And that feels good.”