One of the main complaints against Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is its refusal to take a stance—was the atomic bomb truly worth the end of World War II? Was the titular character to blame for the death and destruction that followed his creation? But ultimately, “Oppenheimer” shines in its ambiguity, its refusal to answer these questions. Instead, multiple facets are explored and dissected, and it is left up to the audience to consider their own stances on the complex relationship between science and politics. The resulting film is a whirlwind, somehow managing to strike a nearly perfect balance between thoughtful and epic.

To distinguish between his two major timelines, Nolan makes the bold choice of putting nearly half of his film in black-and-white. These scenes represent the timeline from the point of view of Robert Downey Jr. ‘s Lewis Strauss, the closest thing the movie has to an antagonist. The scenes in color are from the point of view of Cillian Murphy’s titular character.

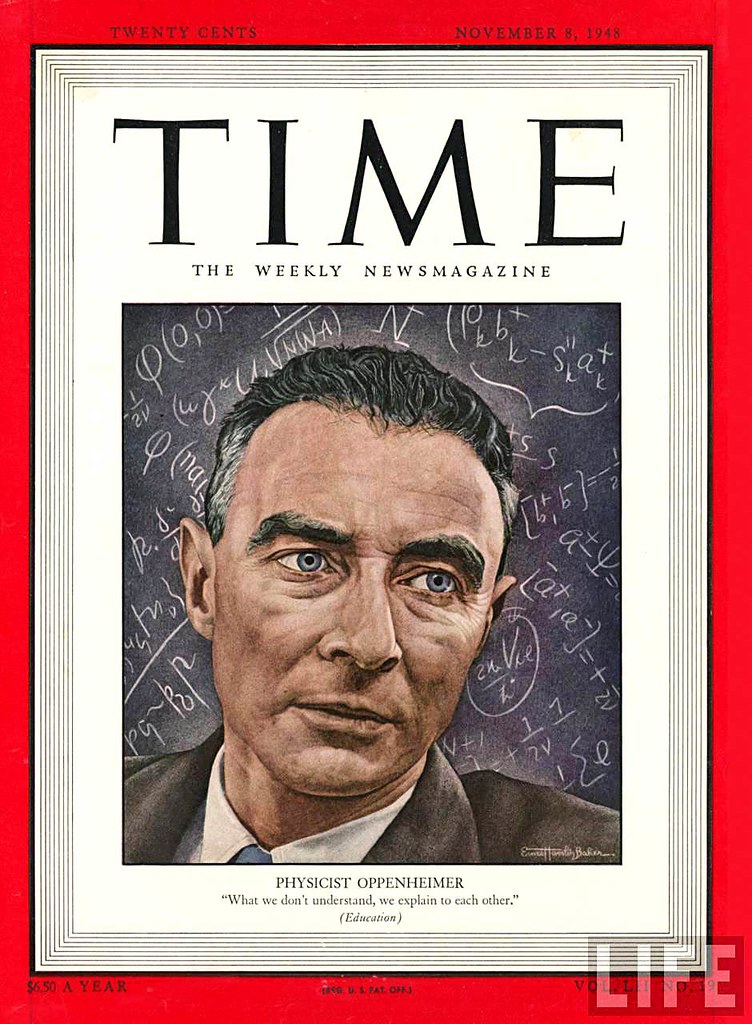

Murphy, in addition to his incredible resemblance to the real J. Robert Oppenheimer, delivers his lines perfectly, but he shines in his character’s quietest moments. Murphy’s expressions manage to convey the complex emotions implied in his role; a combination of guilt, pride, and wonder at his own creation. Downey is incredible as Strauss, and his obsession with revenge over feeling slighted by Oppenheimer is perfectly portrayed in every scene, a clear underlying motive to every action Strauss takes. Emily Blunt as Kitty Oppenheimer and Florence Pugh as Jean Tatlock also stand out in their roles, despite the relatively short amount of time they appear on screen. While the movie is ultimately centered around a man and has no hopes of passing the Bechdel test, the women in “Oppenheimer” are fascinating, multi-faceted characters, with their own distinct personalities. The bonds between Oppenheimer and Kitty, as well as with Tatlock, play a key role in understanding Oppenheimer and his inner battles and motivations, as well as his connection to the Communist Party. His relationship with the Party is also a major conflict in the movie, but Nolan manages to make even the political debates full of tension and gravity.

One of the best features of “Oppenheimer” is the stunning use of music and sound throughout. Ludwig Göransson’s soundtrack envelops the audience in the epicness and gravity of each climactic moment in the film. But the most incredible moment of the movie comes in total silence. The first major part of the story culminates in the Trinity Test, where the first atomic bomb is exploded in the middle of New Mexico. The music rises to a crescendo as the timer counts down, then clouds of fire fill the screen and the music drops away. There are several beats of silence as the scenes shift from face to face and Murphy says Oppenheimer’s most famous line—“and now I am become death, destroyer of worlds”—before the shockwave hits and the chaos resumes.

Nolan somehow manages to make a convoluted timeline, a three-hour runtime, and incredibly complex lead into a heart-stopping thriller. The large cast and overlapping storylines may be confusing to some viewers, but ultimately, Oppenheimer is worth every second of its runtime.