Close enough

The evolution of my name and Sri-Lankan identity

April 30, 2020

I have the type of name that scares substitute teachers. When they get to my name on the attendance list, some will pause, and others will spell my name out loud. Only the bravest will attempt to pronounce it.

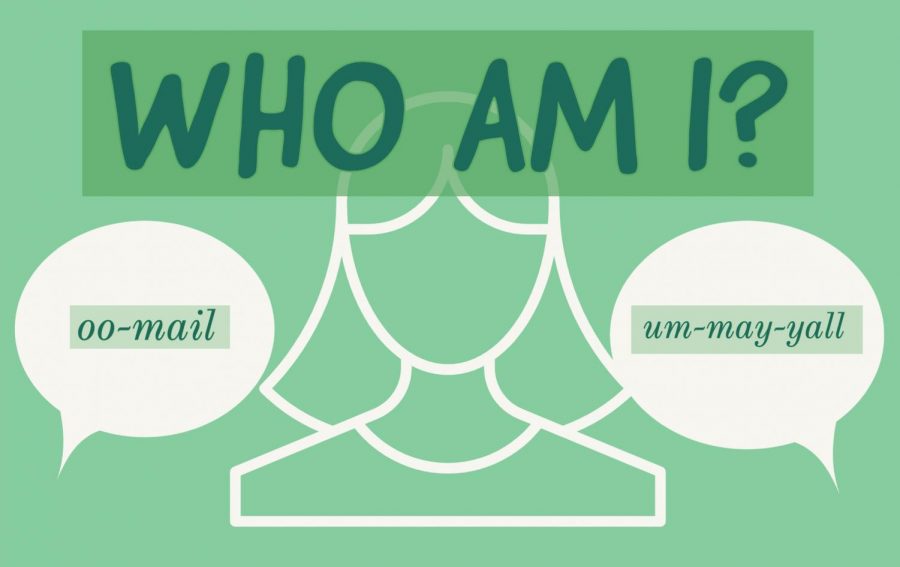

My name is Umaiyal (um-may-yall) Kogulan (co-gu-len). While I now find humor in all the pronunciations of my name, growing up, it was a constant reminder that I will always be a foreigner in my own country.

My kindergarten teacher was the first person who Americanized my name. She had thin blond hair, wore chunky gemstone jewelry and always had a scarf draped around her neck. In my young eyes, she was a true “American.” When she was unable to learn the real pronunciation of my name, I felt as if America couldn’t accept my full Sri Lankan identity.

Instead of continuing to correct her, I simply accepted my new Americanized name, Oo-mail. I hated it. My name, intended to honor the Hindu goddess Parvarthi, was shape-shifted into gibberish. However, at the time, I thought it was the price I had to pay to assimilate into American culture.

I went through school carrying the burden of my name. Kids would make fun of my name at recess. Some teachers would ask me to go by a nickname to make it easier. By 5th grade, I would respond to mail, mayo or anything that remotely sounded similar to my name.

It got worse in middle school. My middle school volleyball coach gave up attempting to pronounce my name at tryouts. So for two years, she called me “U” at practices, games and even the awards banquet. I will forever remember images of our opponents’ confused faces when she yelled “U go for the ball.”

As time passed, the two different pronunciations started to represent the duality in my life. Umaiyal (Oo-mail) was American. She wore sparkly Justice clothes, made loom bands with her friends and ate lunchables. Umaiyal (um-may-yall) was Sri Lankan. She wore half saris, did classical dance and ate dosas.

I became incredibly frustrated living between this duality. I wanted a name that naturally flowed off the tongue, a name that was printed on genetic keychains at gift shops, a name that didn’t make people double-take.

When I went to high school in a new town, I thought of it as a restart. I started introducing myself as Maya. Arrogantly, I thought it would solve my identity crisis. However, I will always have brown skin. I will always be Sri Lankan. I couldn’t hide my cultural insecurity behind a white name. Although it made ordering at Starbucks easier, I was still trapped between two opposing cultures.

Over the past year, going by Maya has taught me one thing: I will forever live between two cultures. I can’t change that with my name, clothes, or friends. Slowly, I am beginning to learn the beauty of belonging to two cultures. It is a privilege not a burden.

Children shouldn’t be conditioned to resent their cultural heritage. That starts in kindergarten classroom. The simple act of learning the correct pronunciation can change their self-image. The truth is if we can learn to pronounce names like Timothee Chalamet and Arnold Schwarzenegger, we can learn to pronounce all names, including Umaiyal Kogulan.