Coming to terms with hidden biases

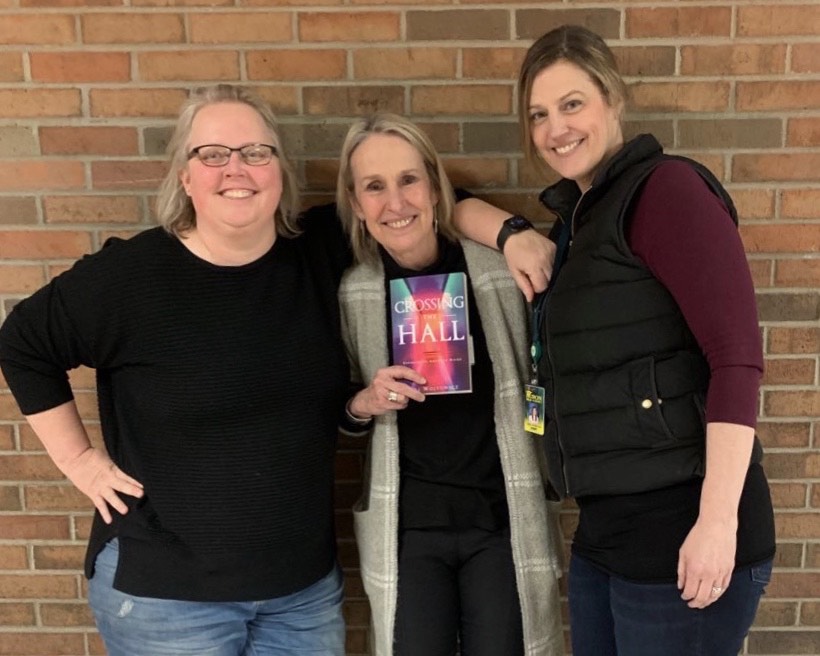

Author and former teacher Lori Wojtowicz (center with CP Personal and Professional skills teacher Ms. Garrett(left) and DP theory of knowledge teacher Ms. Anderson(right).

April 10, 2020

When thinking about biases, it’s easy to focus on white supremacists and the Black Lives Matter movement. But judging a person based on their religion, socioeconomic status or race is much more nuanced. It took about 10 years of teaching for author and former Huron teacher Lori Wojtowicz to realize her personal biases.

“I thought, why didn’t I ask why there weren’t Black kids sitting in my AP class,” Wojtowicz said. “It was because I was comfortable. It makes me sad that it took me so long to ask these questions…The divide in our school became very apparent to me.”

Wojtowicz’s book “Crossing the Hall: Exposing An American Divide”, discusses events in her life where she recognized the disparity in socioeconomic classes at Huron. As a former white teacher, Wojtowicz now goes to schools around the country talking to other teachers about how they can uplift all of their students regardless of race, socioeconomic status, past educational record and out of school responsibilities.

Wojtowicz visited some of the IB Theory of Knowledge and Personal and Professional Skills classes on Feb 19 trying to help students recognize their own personal biases. She asked the students to imagine themselves in different experiences. She asked the students how they would feel going to a party where everyone was a white supremicist or an ex-con. Or whether they would be comfortable dating someone who identified as a party member opposite from their own.

“I just believed that I was an open minded person, and I trusted that without investigating deeper,” Wojtowicz said. “I don’t want to tell [students] what to believe. I just want them to question their own beliefs and be comfortable after they’ve questioned them.”

Christy Garrett, the Career Program Personal and Professional Skills teacher, taught at Huron when Wojtowicz was the African-American Literature teacher. Garrett brought Wojtowicz in for a session with the seniors in the Career Program because it related to the Thinking Processes and Intercultural Understanding part of the CP curriculum.

“A big part of the Thinking Processes curriculum is how do you know what you know, and when you apply that to Intercultural Understanding you look at not just race but also religions, disabilities and socioeconomic problems,” Garrett said. “Teaching people that ability to try to put yourself in somebody else’s shoes is really important — instead of being defensive, being able to listen to what their experiences are and then learn from that.”

Career Program senior Manal Shaikh was initially interested in what Wojtowiz could provide to the discussion on race as she is white. However, the discussion led to a greater understanding of the different students at Huron overall for Shaikh.

“I was really enlightened in the end,” Shaikh said. “It really made me realize where my personal biases are and helped me explore a different part of myself.”

Wojtowicz grew up in Grand Rapids which is predominantly white and wealthy. As a child, she was taught by her parents that everyone is equal. Later as she was going off to college her parents told her that she couldn’t bring a Black person home with her. She then realized the biases that had been perpetuated by her own family. She later went to Kalamazoo college to study education but was never confronted with her own biases.

“Issues of race rarely surfaced even in my education classes,” Wojtowicz said. “However, I do think Kalamazoo [College] taught me how to think, which aided me in confronting my own ignorance.”

As a former teacher of African-American Literature, Advanced Placement English and Psychology, Wojtowicz taught a wide range of students, including some of those who were paraplegic, homeless, and stand-in parents. Growing up in an upper-class family these factors were never a reality for Wojtowicz. Regardless, she worked to provide as many opportunities to every student that she had.

“I would start every [African-American literature] class the same way: ‘I bet you’re surprised I’m teaching African-American literature,” Wojtowicz said. “Once it was out there, then I could say I think I know more about the literature than you do at this point, but I know nothing about the experience of being Black.”

Wojtowicz isn’t afraid to talk about these realities, not only in America and Michigan, but also specifically at Huron. For instance, a former white student of Wojtowicz wanted to sign up for Wojtowicz’s African-American literature class but was discouraged by their counselor at the time because the class would be ‘‘too easy’’ for him. The counselor had decided this without meeting the teacher or understanding the class dynamic.

“That means that you have it in you that the classes that Black students take are easy,” Wojtowicz said.“That implied to me so much prejudice that I don’t think that counselor intended, but what’s missing is that awareness.”