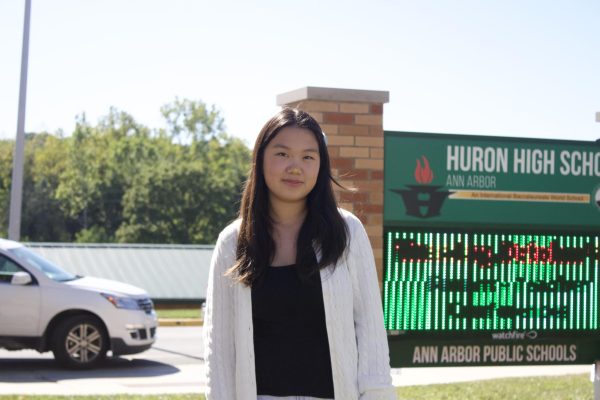

I was born on the cusp of the next decade, of the 2010s. The 2000s were never something I personally experienced, unless you count me being in the womb. And yet when I watched “Dìdi” (2024), director Sean Wang’s first full-length feature film, I could feel what it would be like to grow up in the late 2000s: when YouTube was filled with grainy amateur home videos filmed on hand-me-down Sony Camcorders; when someone’s MySpace page was their entire identity and waiting anxiously to hear a ping on a silver Motorola flip-phone.

Dìdi embraces all of the parts of cringy adolescence unflinchingly. The film tells the story of 13-year-old Taiwanese American Chris Wang, throughout the summer before 9th grade, from awkward first interactions with a girl he likes, tight-wound relationships with his family, friendship troubles, and most importantly, finding himself.

“You’re old enough to know better and young enough to not care,” Sean Wang said about being 13, in an interview with NPR. And that is what Dìdi explores: the in-between. Chris is boyish, with a mouthful of braces and a shaggy bowl cut. But he is also something more, someone he is slowly growing into and learning to become.

The title of the film, “Dìdi,” means little brother in Mandarin, and is both a common nickname and an affectionate term in Chinese households. Chris is regarded affectionately as “Dìdi” by his mother, Chungsing, and paternal grandmother, Nǎinai.

Despite his multitude of names — known as “Wang Wang,” to his friends, “bigwang510” on MySpace, and “Dìdi” to his family, Chris still hesitates when introducing himself to new people, saying “um… Chris,” when he meets a trio of older, cooler skater boys he desperately wants to impress, lying that he “films” skateboard videos.

While the film features a multitude of components, a main theme throughout the film is Asian-American identity and both the struggles and joys that come along with it. At the dinner table, Chris uses a fork, unlike the rest of his family who use chopsticks — a subtle nod to the familiar disconnect many second-generation immigrants and Asian-Americans face.

On an awkward first date with the girl he likes, she tells him, “you’re pretty cute… for an Asian.” I found this incredibly ironic — his crush, Madi, is half-Asian herself. Yet, she feels that she is in a position and white “enough” to compliment Chris in such a way. After this sobering experience, Chris lies that he is half-Asian, causing the older group of boys at a grown-up party of which he is the youngest in the room, to chant in circles, “Half-Asian Chris! Half-Asian Chris!” as he chokes down a cigarette.

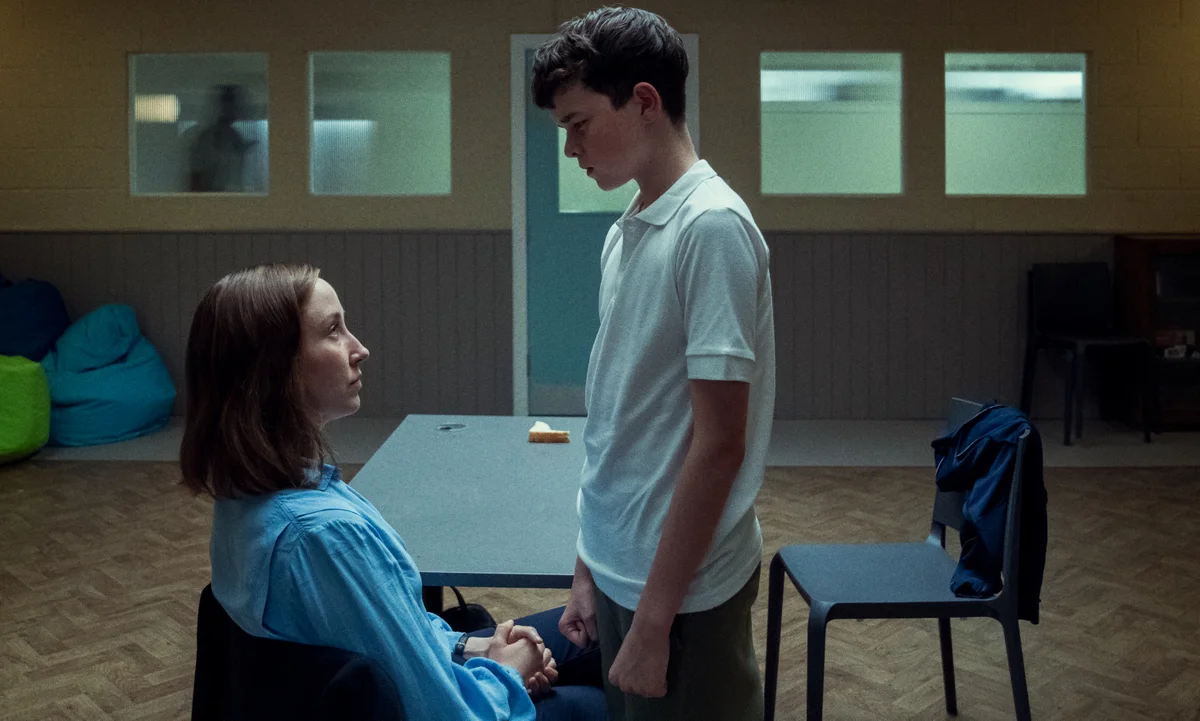

In the Wang household, relationships are loving yet strained. His mother, Chungsing, raises him and his sister alone, with the exception of Chris’s paternal grandmother, Nǎinai. Chungsing is a first-generation immigrant, stay-at-home mother, and painter. The film explores what immigrant parents sacrifice for their children; there is a scene where Chungsings tells Chris what she wonders her life would be if she had not met his father, if she had not him and his sister. She asks, “What would have happened to my dream?”

The scene is bleak, somber, and unbelievably raw. The pair sit at the edge of a beige, floral room in the mild light of the early morning. I find that it is the all-encompassing moment of the film, of forgiveness, discovery, and unconditional love.

While “Dìdi” captures all of these embarrassing, coming-of-age moments with confidence and almost a sense of beauty, there doesn’t seem to be much else to be said. Though Wang denies it, it’s clear Chris is a substitute for Wang himself or at least some sort of version. This heavy lens of semi-autobiography causes the film to lack in certain aspects: it tells a story, but not much else, at least not in the way most would expect.

Chris doesn’t truly find himself at the end of the film. He doesn’t accept his Asian American identity nor does he completely make up with the friends he drifted away from. The story doesn’t wrap up neatly like most would expect from a coming-of-age film. Instead, Chris begins the first day of school. He smiles, his shiny white teeth braces-free, fulfilled from the roller-coaster of a summer he had before freshman year. He’s not quite there yet, but he will be, eventually. As we all are.