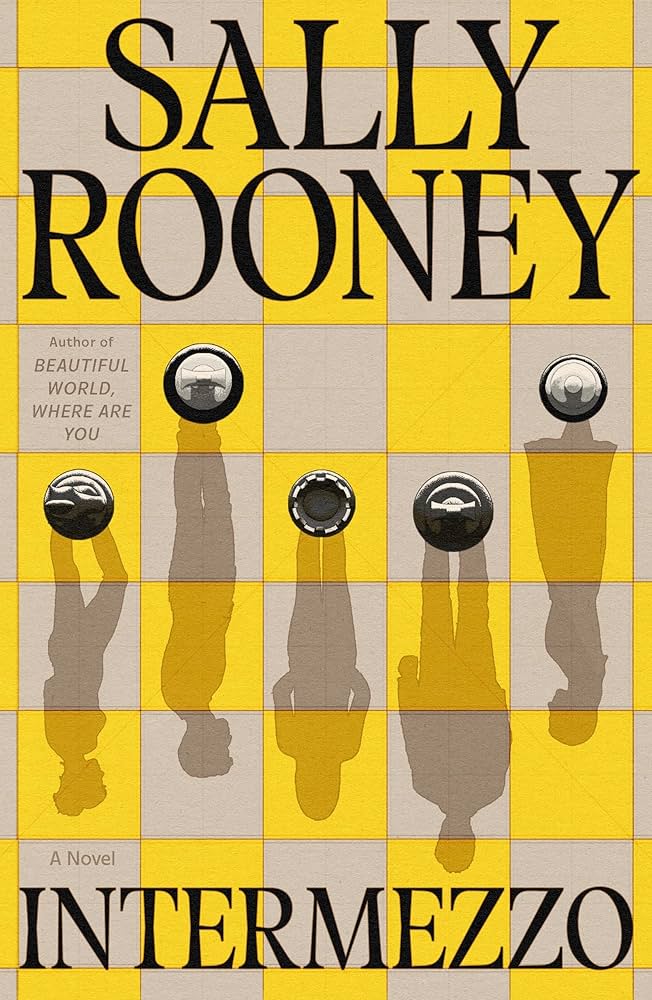

At just 33 years old, Irish author Sally Rooney has achieved international success, with her 2018 novel Normal People selling more than one million copies in the UK alone and receiving a 2020 television adaptation. But with great success also comes controversy, and Rooney has more than most, and her most recently released novel Intermezzo has not escaped this criticism.

While the author has hundreds of thousands of diehard fans, Rooney is also a name that is frequently bashed in online literary communities such as Goodreads, the popular book reviewing site, and BookTok, the niche of the social media app TikTok where book lovers gather to review books, share recommendations, and more.

There are several popular dissensions regarding Rooney that seem to be most people’s issues with her writing. Firstly, Rooney is iconically known for her complete refusal to employ quotation marks. That’s not to say her books have no dialogue — rather, the dialogue is written just as any other book, but it lacks quotation marks to notate that it is, in fact, dialogue. Readers frequently express frustration with this stylistic choice, calling it annoying, pretentious, stupid, and more. However, as Rooney’s books are all ultimately character studies, rather than being plot-focused, the author’s fans argue that the choice aids in representing the prevalent miscommunication between characters. Personally, I enjoy the lack of quotation marks, as it makes for a more seamless and integrated reading experience, also feeling more like I am more pulled into the story and the characters’ thoughts, rather than just reading dialogue on paper.

Other prevailing complaints about Rooney include her often pretentious writing, and many also feel as though her writing feels too “white,” added to by the lack of characters of color in her novels.

However, I have never faced such issues when reading Rooney’s works. Although I acknowledge her often pretentious writing style and lack of diversity, I do not see them as defining problems that overshadow the things I love about her books—namely her ability to inspect human relationships at microscopic levels and build characters so comprehensively, without explicitly stating much, that the reader can understand and empathize with the characters’ behaviors and decisions despite them often being essentially dislikeable.

Rooney’s newest novel Intermezzo, published Sep. 24, 2024, continues her exploration of the human condition through the characters’ daily lives and interactions. The novel follows two brothers, Peter and Ivan Koubek, who have, at the debut of the novel, just lost their father to a years-long battle with cancer. Peter, 32, is a successful lawyer juggling convoluted relationships with two different women, one a 23-year-old homeless college student, the other a 32-year-old professor dealing with chronic pain from a past accident. Ivan, 22, is a washed-up competitive chess player who begins a relationship with a 36-year-old woman he meets at an exhibition match.

Grief for their father pervades the brothers, each in different ways but causing both to question and reflect on their pasts, futures, and what gives value to their lives. Due to their completely separate lives and mutual complicated dislike, the brothers mourn alone, unable to confide in and be vulnerable with one another for most of the book.

The novel is told from three points of view — Peter, Ivan, and Maragaret, the 36-year-old divorcée Ivan strikes up a relationship with. Rooney manages to seamlessly transition between perspectives while still giving each character their own distinct voice. Peter’s chapters are written in a choppy train of thought style, involving short, staccato, often incoherent sentences that mix with the lack of quotation marks to make Peter’s narration feel very stream of consciousness, as if we are surrounded by his inner monologue. In contrast, Ivan’s perspective reveals his thoughtful and logical nature to the audience, but also his anxious, rambling nature. In the midst of Ivan’s chapters, Margaret’s perspectives add a calm and assured undercurrent to play off of Ivan’s anxiety and self-consciousness. At the same time, the reader recognizes Margaret’s own uncertainty, guilt, and inner conflict, which Ivan is completely blind to due to the pedestal he puts her on.

An intermezzo, from which the novel is named, is a short, connecting instrumental movement inserted between the acts of a play or movements of a larger musical work. While reading the book, I felt that it was very aptly named — the story seems to follow the characters during a suspended time in their lives, a time between life’s bigger, more important events, simply a time of existence leading up to the main points. However, the book also explores this very idea — is life valuable because of the big, important moments? The events that act as timestamps in our lives?

The novel dipped into a discussion of the very meaning of our existences, especially through Margaret’s perspective, wherein she frequently ruminated on the purpose of her life, and the fact that life seems to be more a mere amalgamation of random, everyday occurrences. “What if life is just a collection of essentially unrelated experiences?” Rooney writes, through Margaret. “Why does one thing have to follow meaningfully from another?” And also — “Margaret feels that she can perceive the miraculous beauty of life itself, lived only once and then gone forever, the bloom of a perfect and impermanent flower, never to be retrieved. This is life, the experience, this is all there has ever been.”

In this way, the novel refutes the seemingly collective agreement of humanity that there is some meaning to our lives, some larger purpose of each of our existences. It goes against its own name, Intermezzo, exploring the idea that this period of time in the characters’ lives is in fact not a sort of “intermezzo” or intermission between milestones, but rather that it is just as important as every other moment in their lives, because none of the moments are ultimately truly important or meaningful.

“Had believed once that life must lead to something,” Rooney writes on page 14, “all the unresolved conflicts and questions leading on towards some great culmination.” Rooney then goes on to, through Peter, scoff at this past belief that his life was ultimately going somewhere, that there was an end goal to be reached that would make everything up to that point worth it. In Peter’s perspective, Rooney views this outlook on life through a fatalistic, cynical lens, discussing the world in a scornful and pessimistic manner.

“The men frantic with insecurity, rehearsing the same old jokes in increasingly strained voices, desperate to catch the senior’s eye,” Rooney writes on page 69. “The women, nearly worse: giggling along. The meaningless lives people live. And afterwards, oblivion, forever. Futile rage, at nothing. Directed one way or another, what’s the difference.”

However, through Ivan’s chapters and his self-discovery through his relationship with Margaret, Rooney flips the tone and explores the view that life is beautiful due to its ultimate meaninglessness, that it is almost a relief that there is no bigger, ultimate purpose to our existence and we can simply enjoy and value the small things until we ultimately meet our inevitable ends.

“Strong, powerful feelings of happiness, satisfaction, protectiveness,” Ivan narrates on page 54. “It could all be very ordinary, in the aftermath of mutually pleasant episodes like just now. Or even if it’s rare, to have a few times in life and no more, still worth living for, he thinks. To have met her like this: beautiful, perfect. A life worth living, yes.”

Rooney, known for her manipulation of human relationships, demonstrates the ways in which Margaret’s entrance into Ivan’s life causes his worldviews to become more appreciative and hopeful. “The inexchangeable pleasure of her conversation,” Ivan muses to himself while taking a walk with Margaret. “Just to walk the streets saying things, anything, just the act itself, walking together at the same speed, and talking, purely to amuse and please one another, to make each other stupidly laugh, for no further accomplishment, no higher purpose, to let their words rise and disperse forever in the damp brackish air.”

Overall, the multifaceted, undisputedly flawed, and often dislikeable characters of Intermezzo’s cast and their convoluted relationships with one another, set against the backdrop of the novel’s greater theme of appreciating life despite its futility, made for a fascinating read. Although Conversations with Friends remains my favorite Rooney novel, I particularly enjoyed the stylistic choice of staccato, stream of consciousness-esque writing in Peter’s chapters and the focus on a brotherly relationship of Intermezzo. Although her writing isn’t for everyone, it cannot be denied that Rooney has a deft control of characters and how they interact to shape a dynamic relationship, as well as fascinating thoughts regarding the human condition and society.