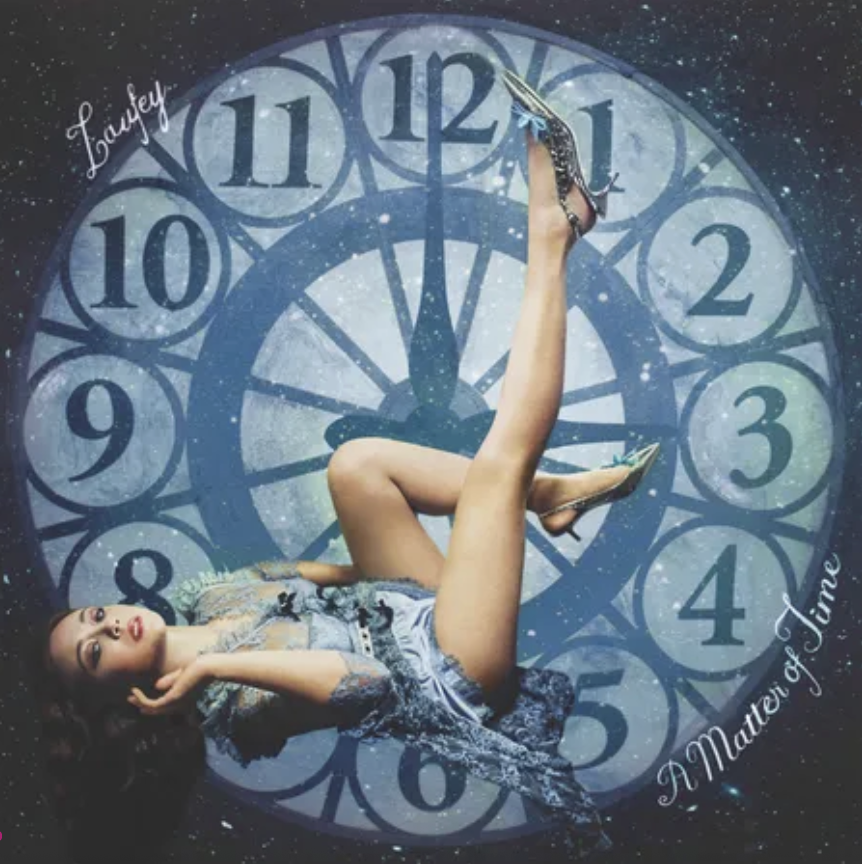

Jazz is dead, and Laufey has come to its gravestone with a shovel. Listeners have crowned her the savior of jazz, her streams have dubbed her the most famous living jazz artist. With her Chet Baker-esque romantic sound and her lush orchestral arrangements, Laufey has proven herself to be jazz’s princess–at least, that’s the rhetoric that has been running circles in the music world. Since her rise, I’ve been in the unfortunate position of questioning if this title is accurate. I’ve found myself time and again asking “Is Laufey jazz?”

Jazz, while a diverse and versatile genre, has a few pillars that make it what it is. Music critic Stanley Crouch described the setup of jazz arrangements as “a great improvising voice, the person who organizes the music, the composer, the band leader, and then there’s the interaction between the audience and the music itself.” Collective decision-making as well as improvisation are key players in jazz music.

Laufey uses aspects of this in her work, most notably improvisation in her voice as well as the bebop vocabulary she uses in her most popular songs. This goes off gear when we note how her arrangements are set up. Laufey uses lush orchestral arrangements in a lot of her music, which makes sense considering her classical background. These arrangements, while beautiful, don’t allow for improvisation or collective decision-making that so much of jazz is built off of.

“Ensemble language of music is partially composed and partially improvised {which} shows how powerfully people can be themselves and be a collective at the same time,” Crouch said “That’s where the real force of jazz comes from.”

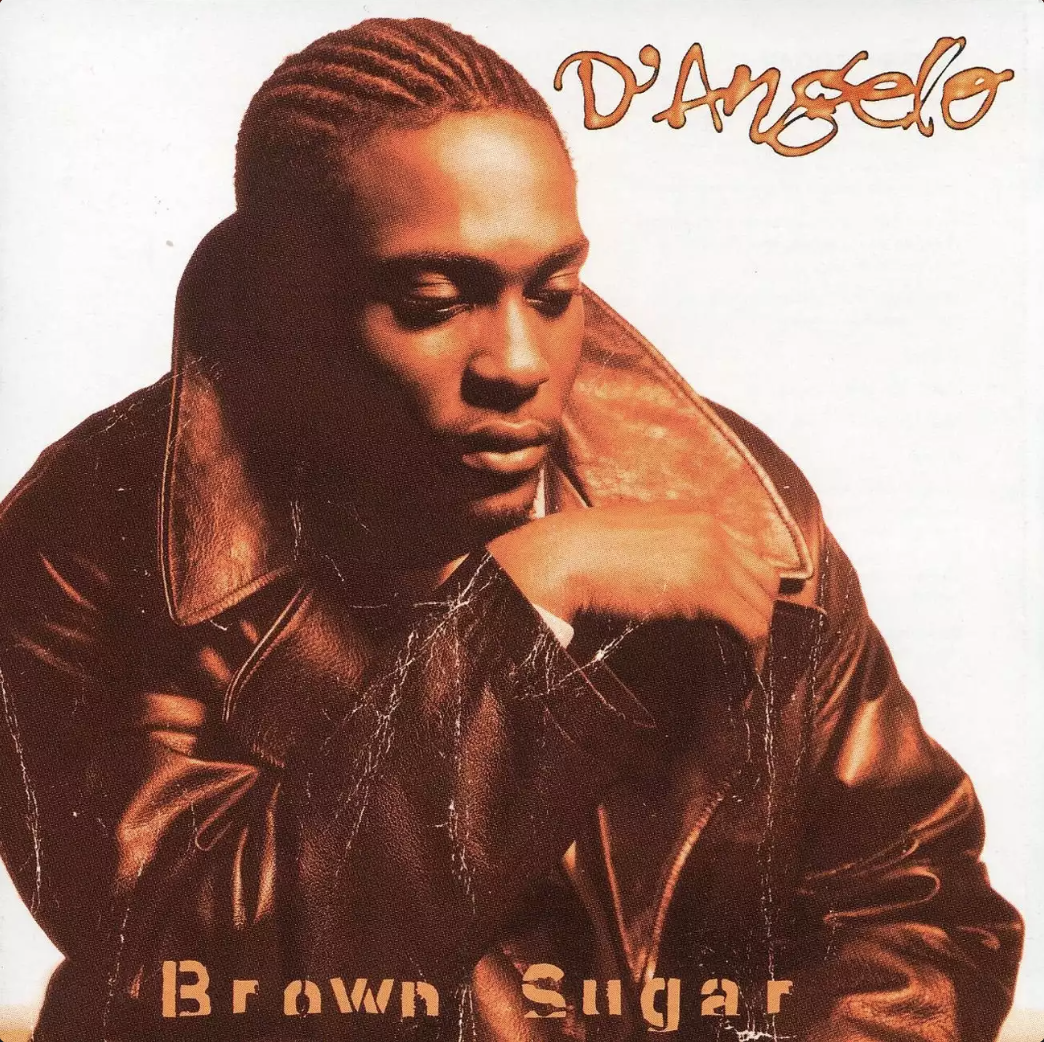

There is also something to be said about a half-Asian artist being seen as the face of a genre so heavily rooted in Black culture. This isn’t to say that non-Black artists can’t participate in jazz, but to put a non-Black artist on a pedestal and say the genre is dead when Black artists are making the same music, and thriving, is off-putting to say the least. For example, Samara Joy Best New Artist/Best Jazz Vocal Album at the Grammys last year; she’s been around for as long as Laufey and is categorized under the same genre, why doesn’t she get the same acclaim?

Every few decades, a “savior of jazz” is born. It happened with Wynton Marsalis in the 80s, Norah Jones in the 2000s, and it’s now happening with Laufey. Pianist Marcus Roberts experienced a similar labeling at his peak. He was assigned the label ‘young lion’ and when asked what he thought of it, he replied: “I’ve heard it, I don’t ascribe to {it}…it’s more of a marketing term.” So much of Laufey’s influence in the genre comes from how she’s been marketed, how she’s marketed herself.

“Jazz itself is a marketing term like most genres, they’re used by record labels to define music into categories so it’s easier for people to understand,” said Jon Blanchette, a Michigan-based jazz drummer. Blanchette went to Berklee the same year as Laufey, and got to witness her rise in real time. He noted in our conversation that she was only studying classical cello at the school.

“Calling her the savior of jazz is really marketing her towards younger audiences,” he continued “but I don’t necessarily think that she would even call herself a jazz musician.”

But she has, and she continues to. Laufey, while she makes beautiful work, sells the aesthetic of jazz rather than actual jazz music. She paints a picture of a smoke-filled jazz club set in the 1920s, something far away. In reality, jazz is so much closer to us than that. From your home, you can watch Live at Emmet’s Place, an exclusively live-streamed show that features some of the most talented jazz musicians of our time from artist Emmet Cohen’s bedroom. In Ann Arbor, you can visit the Blue Llama or the Habitat for the actual jazz club experience. Jazz never died, in fact, it’s thriving.

Amelia Bai • Feb 23, 2025 at 2:51 am

aghhhh lede gets me everytime