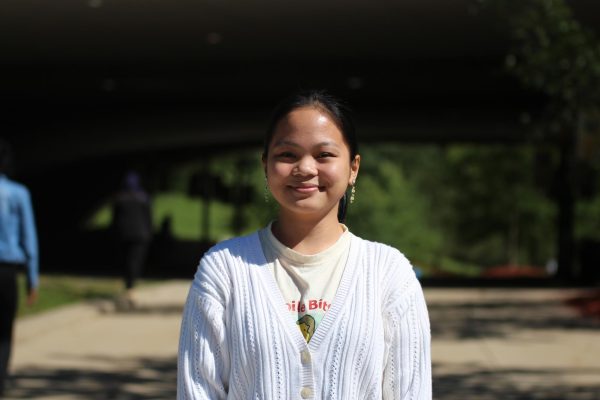

Merriam-Webster defines the word parallel as “similar, analogous, or interdependent in tendency or development, exhibiting parallelism in form, function, or development”. For Randa Hourani, her own definition of parallel is: Growing up in a war-torn country where school was never an option, then finding her way back to the four walls of school, teaching as an educator.

Hourani, 63, a substitute teacher in Huron, knew and understood that the first two years of her teenage period were not as normal as what others would think. She never got to hang out with her friends and be naive like how kids her age would be, school was not as accessible like how it should be today, and going out for outdoor activities was stupid. Instead, Hourani, 13 when it happened, had her days filled with the sounds of bombs and gunshots constantly ringing and bouncing within the four walls of her home in Beirut, Lebanon, deaths being often reported, families crying out for justice, and her country was on the brink of being partitioned.

“In 1976, I came to this country because my dad left during the Civil War, brought my mom and my other siblings (three brothers), and I stayed [in Beirut, Lebanon],” Hourani said, a nostalgic smile on her face. “He’s afraid – he was so scared, scared to bring us [to the U.S.]. So, I basically stayed there with my two other (younger) sisters, then the war escalated, so we came here.”

It was 1975 when the Lebanese Civil War happened. The tension between the country’s Christian and Muslim populations was rising until Phalangists, a Lebanese Christian political party, attacked a bus carrying Palestinian refugees, who were on the side of Lebanese Muslims, on their way to a camp. The armed conflict lasted for a decade and half, leading to 150,000 casualties. Hourani was 14, one year into the war, when she left her home with her other two younger sisters on the 22nd of February 1976 through her dad’s EB1 visa, starting an entirely different life in Dearborn, Michigan with her family.

“I was sad – I thought that no one should be happy,” Hourani laughed, recalling what she had felt about the whole situation back then. “I didn’t know anybody. My dad knew people, that’s why we came to Michigan.”

Back in her time, Dearborn was not exactly very nice to Arabic people. Hourani had a clear memory of the racial discriminations she suffered from, also having a fair share of the other race riots she had witnessed.

“We were a minority at that time,” Hourani said. “There used to be bloody fights everyday. The White kids used to call us “camel jockeys,” [chanting] ‘Go back to your country!’. The people in Dearborn back then were very racist – they targeted minorities like Muslims. They didn’t sell anything to us. So mean, you know?”

Growing up, Hourani has had really interesting and memorable experiences that were unique to her culture, but is something that is unusual for many other people of different cultures.

“My dad arranged me in a marriage; he was 32, I was 18,” Hourani said, smiling knowingly, aware that the age difference was quite uncommon for younger people. “It’s common [for my culture], but now, it’s becoming better. My family knew his family. It was okay, but I wouldn’t do this to my kids. Imagine: you get married, and you don’t know that person? I was like, ‘No, I didn’t even know him!’ It was hard.”

Despite barely knowing English when she lived in Dearborn, Hourani did not let this interfere in her way to pursue education as a student in Fordson High School where she had to take three hours of it and another foreign language, which was French. She graduated, then went to Wayne State University in Detroit where she majored in Business. Magically, Hourani’s path was suddenly redirected to teaching.

“So I took French into business,” Hourani said, laughing. “I was not that good in business! Then, my friend told me that they have these workshops and they’re recruiting people (to become teachers). So I go there, and they proposed and said that ‘if you switch, we’ll give you more salary’. [I was like] ‘Switch to what? No!’ It never even crossed my mind. It was very hard, [but] it was good. At least they gave you [an] opportunity. We lost everything in the war, so I needed the money.”

Just like that, Hourani now had a teaching degree. However, there was a halt before her teaching journey even started. She did not get to teach after graduating as she had to move to San Diego, California in 1986 with her husband and two children.

“He got a job in San Diego, so we moved,” Hourani said. “I had a son who was two years old and a baby who was four months old. We stayed there for a couple years, then he got laid off, so we came back [to Michigan] in November after three years of graduating. They needed a teacher in Detroit, I applied everywhere, and it was hard. I ended up getting a job, November 2nd, [that] I signed. He stayed there because he didn’t like Michigan.”

Still vividly ingrained in her memory, Hourani remembers every moment she struggled financially when she came back to Michigan while also having to raise her two young kids alone without her husband.

“We lost so much money,” Hourani said. “Luckily, I didn’t sell my house [in Dearborn when we left]. Everything I had, my clothes, I borrowed from my sister. To me, it’s important – and I had nothing.”

During her job search around Detroit in 1987, she finally found an opportunity that would become her home for most of her teaching career. Within the halls of Mumford High School, Hourani had now begun her teaching career – her first teaching job.

“I stayed at this school as a teacher for 21 years,” Hourani said. “It was a good school, a neighborhood school. It was something. They had a merit program, like between honors and regulars. You have to have a foreign language, so that was good [because I was a French teacher].”

Hourani taught at Mumford for two decades and a year, then switched to Henry Ford High School as the state took over her first school. She spent four years teaching in Henry Ford before she transferred to Renaissance High School, also teaching there for four years.

“I retired in 2016,” Hourani said, wearing a proud smile. “I worked from 1987 to 2016 straight.”

Hourani’s 29-year teaching career had brought her many good memories that she still continues to look back to up to this day. When asked what were some of the most memorable moments from her almost three decades of teaching, Hourani can only think of two certain stories.

“One kid had an introduction in front of our class, and said that he was stabbed in his stomach,” Hourani said. “We didn’t believe him, so he showed us. He was like ‘Here. I almost died in Turkey.’ He was a Syrian who had to go to Turkey, so he could come here [to the U.S.]. Turkish people were mad at him – didn’t like him there. He was stabbed, and he showed us his stitches.”

Additionally, she had also heard a “crazy story” from her sister who also became a teacher like her, also proudly sharing that “her two [younger] sisters followed her path”.

“10 years after Iraq was bombed, one of my sister’s kids (students) was born in captivity in prison,” Hourani said. “He didn’t know anything, and he had trauma because it was just underground. He was born in an underground prison in Iraq, his mom was pregnant with him when she was captured in Iraq. So, he was born there, and stayed there. My sister cried – she was tormented, and tried to help him because he was like a wild child.”

Hourani still looks back on the moments Middle Eastern people suffered from wars with a tormented heart. Aside from these two stories, Hourani can “never forget” how much she suffered as an Arabic teacher in the United States after 9/11 happened.

“I had a hard time in 2001,” Hourani said, “After 9/11, they hated me; I was the only Arabic person in the whole school. The first two weeks were hard – even the teachers hated me. I was like ‘It’s not my fault!’ When I walked into the teacher’s lounge, they would be quiet. It was horrible; I was like ‘Are you talking about me?’ One of my students said ‘We’re gonna kill you all!’, so I paid the price of being Arabic. It took me two years to tell them I was Arabic. I thought they were gonna put a blog (about me).”

Despite the racial discriminations she had encountered and been challenged with, Hourani still loved being a teacher and continued her career. Certainly, like other teachers, Hourani also had what she thinks her favorite or best part about teaching is. For her, it’s the “difference she gets to make to others” despite the cultural differences and gaps.

“It’s that: you made a difference in someone’s life,” Hourani said. “Because I feel like I did, honestly. I’m giving confidence to someone and helping them, and they see you, you know? They’re successful – that’s how I feel. You’re not only teaching the language, you’re teaching about life. I always like to teach about me (my experiences), and teach them. It’s like, you did something, and they appreciate you. They appreciate you more later on.”

This sense of fulfillment had encouraged Hourani to continue as an educator, though not as a teacher anymore, but now as a substitute teacher.

“The best thing about subbing is you feel like you’re still in the loop; you’re still with the young people,” Hourani said, giggling. “And also, you don’t have responsibilities, but you still feel alive. And then you get your pension!”

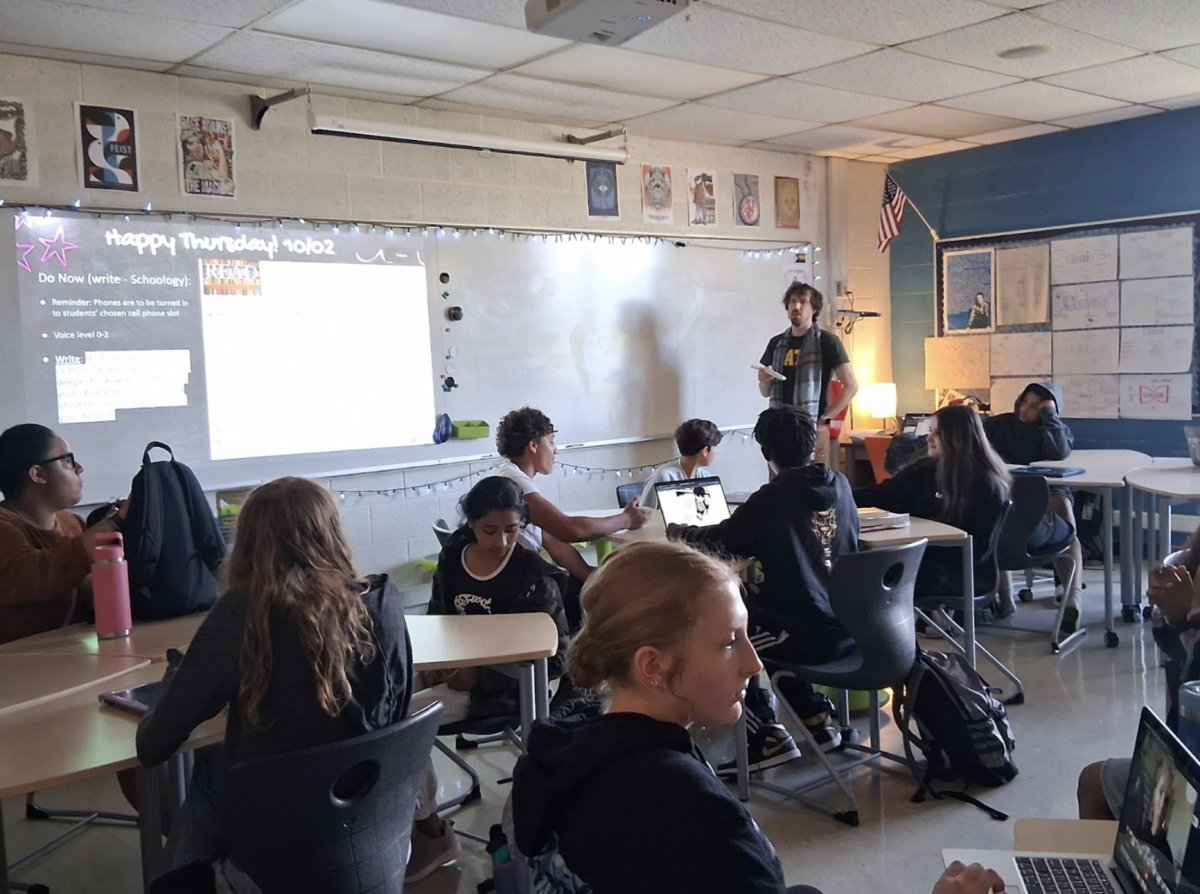

And that was how she got to Huron. Hourani now subs for certain foreign language classes in Huron High School, also filling in for Plymouth High School and Canton High School as a substitute teacher sometimes.

Midway through the interview, as she shares her stories on the people from the Middle East coming into the United States to escape wars and other conflicts, Hourani thought of the perfect word that is befitting for their whole situation. Similarly, as she realizes it was the same for her too, like a Eureka moment had just gone off, Hourani took a pause for a moment, before nodding with a warm look, eyes crinkling with her big smile.

“Refugee,” Hourani said, in a trance of nostalgia. “Yes, I was a refugee.”