Part 1

Smita Malpani felt “unmoored” after moving to Ann Arbor with an 18-month old, where she was doing consulting work on and off. Six years later, with two more kids, she was sitting on the floor of her kitchen, playing with her middle son, when her friend told Malpani that she had started teaching part time. Malpani stopped what she was doing and looked up at her friend, who told her that she could email the department chair at Washtenaw Community College and see if they have any open positions. The idea struck Malpani, and she soon started teaching environmental science part time, getting hired on full time when a position opened later.

Malpani grew up outside of Boston, and after going through college and grad school, she lived in India for a few years, working with a local NGO doing village-level community development. After that, though, she was unemployed for a year, and that was testing.

“You realize how much you rely on external validation,” she said. “[You’re used to], ‘Oh, so and so wants to hire me,’ and when you don’t have that, you have to really rely internally on your own sense of self.”

When she had children further down the road, things changed a lot, too. For one thing, she had to stop traveling for work as much.

“It wasn’t as simple as just being like, ‘Oh, I’ll just leave the baby,’” she said. “So I stepped back from traveling for a little bit.”

They moved to Ann Arbor, and Malpani says that she felt like she was just floating without any attachment in the area, until she started working at WCC.

“I love teaching,” Malpani said. “When you walk into the classroom, your sense of self disappears. It’s not about you at all. It’s about the students. And it actually feels like a relief to not be self-centered.”

In addition to being a professor at WCC, Malpani also does consulting work for international development organizations like the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Gates Foundation. She also is involved with the PTSO and events with the Ann Arbor Public Schools.

Malpani says that she sees women’s careers frequently have twists and turns.

“For myself and many women I know, our career paths are not straight, in one way or another, if we’ve had children,” she said. “Often it’s women whose lives get a little knocked off course before they can find their footing again. It’s so easy to fall into the societal expectation that a woman will step back and do all of the household labor and emotional labor of family life. It’s really, really hard.”

Once her kids turned four or five, though, Malpani started to “reclaim” herself.

“When they’re small, it’s almost like your kids don’t know you exist,” she said. “They just need what they need. Mom is like the air you breathe. ‘Of course Mama’s going to feed me, Mom’s going to care for me.’”

Now, she says that they are her biggest cheerleaders.

“As they get older, they realize that they have their own identity,” she said. “And then they look at me, and they’re like, ‘Oh, this person is another human.’ And they are starting to encourage me to go out and do things.”

The flow of Malpani’s work life wasn’t just affected by the changes that come with starting and growing a family. Career-wise, she has faced discrimination in natural resource management, a field that she says was extremely male-dominated until very recently.

“I remember the first big assignment I did after having kids when I went to Liberia,” Malpani said. “I didn’t know if I could still do it, but it’s something that the USAID still refers to 12 years later. You just have to have this internal fortitude. In the absence of external validation, you have to have this internal sense of self that ‘I belong here.’”

Part 2

Dr. Tyese Parnell grew up playing Schoolhouse with her twin sister. Her sister would always play a teacher, and Parnell would be the principal. From that age on, it was pretty clear that her dream was to become a school leader. But Parnell graduated college with a degree in math and computer science because her parents thought that would be a better career path for her.

“So I started out working at Ford for like a year, and I was a systems analyst,” Parnell said. “And I was just like, ‘I cannot do this for the rest of my life. This is so boring. Nobody talks to anybody.’ I knew I wouldn’t be fulfilled doing that.”

So she stopped working at Ford, and she became an educator. She taught math for 13 years, and then did coaching, supporting teachers and other instructional work for three years. After that, she started to enter the administrative side of the field, and was an assistant principal for six years at Denby High School.”

“My dream was to always be a principal,” she said. “But I knew foundationally that I wanted to be in the classroom first so I could learn how I felt supported so that when I had my own teachers, I could find the best way to support them.”

Now, Parnell is the principal of Tappan Middle School. Being a woman in that position comes with difficulties.

“Being a female principal can be a little intimidating, I’m not going to lie,” Parnell said. “As a woman, it’s already different. You always have to work a little bit harder. You always have to study a little bit longer. You always have to prepare a little bit extra.”

One of the reasons she decided to come to Ann Arbor Public Schools was the large number of women in administration.

“When I went through the interview process, I was overwhelmed with a sense of gratitude,” she said. “You walk into the room and the Superintendent’s a woman, the two people under her are women. The executive positions are all women. And besides the [then] Superintendent? They’re all Black. I felt empowered walking into the interview.”

It’s also an extra challenge to be a woman of color in a position such as a principal. When Parnell first started teaching in Detroit schools, she doesn’t remember there being any Black principals there.

“When I got there in 2001, it was predominantly Black in terms of students,” she said. “But teacher-wise, it was predominantly white. I was one of a few Black teachers in an all-Black school.”

Parnell has definitely noticed a lack of diversity within the teaching staff in AAPS, as well.

“A lot of Black people don’t apply for jobs out here,” Parnell said. “I don’t know if it’s an intimidation factor, if the stereotype says, ‘You won’t fit in here,’ even if the schools are very diverse.”

Especially over the last few years, she has emphasized having her staff get to know the students.

“It’s like, ‘You don’t know these kids,’” she said. “‘These kids are different from how you were raised. They go home and their home life is nothing like the home you came from.’ The more we get students involved, that can change the climate. I make sure my [student] leadership is diverse.

Parnell loves the idea of women crowning other women.

“Fix the crown, put a crown on and wear a crown strong,” Parnell said. “It gives [younger girls] the opportunity to know that their crown is coming too.”

Part 3

Kathryn Jones doesn’t remember when she first wanted to become an educator, but her friends do. Years after they had graduated, and Jones had figured out that she wanted to become a teacher, her college friends told her how she had talked about becoming a teacher while they were in undergrad. And once she got there, there were some times when she doubted her choice.

Jones majored in anthropology and sociology in college. After college, she then did “a bunch of miscellaneous stuff.” Jones worked for the University of Pennsylvania medical school as a secretary for a little while, then did work as a court advocate at a rape crisis center. She then got another secretarial job in Minneapolis with a tuition reimbursement program.

“I was a few years out from college, and it felt like it was time to sort of do something a little more career-oriented,” Jones said. “I started taking the classes that I would need to get my Social Studies degree and get my teacher certification.”

After working at a school in Baltimore, in the summer of 1999, Jones and her partner decided to move to Ann Arbor. She visited Michigan before moving to do some networking, and she decided to cold call all the principals in the area to look for a job.

“I printed off my resume, and I remember I went to Dexter, Chelsea, Pioneer, Community and Ypsi too,” she said. “And I just knocked on the door at each school and asked if the principal was in.”

She happened to come to Huron at a time that was convenient for then-principal Dr. Williams, who took her on a tour of the school. By August, she had the job.

She had been teaching for nine years at Huron, when in July of 2008, she suddenly had a heart attack, which was attributed to stress.

Jones was on medical leave into the fall.

“The whole time, I know I was thinking that this was a wake up call,” she said. “For the rest of the calendar year, I was thinking about whether I should keep teaching.”

Jones said that even before her heart attack, she had been debating making a career switch. She had already started taking a few prerequisite classes at Schoolcraft College to go into their culinary program.

“Nothing seemed possible,” Jones said. “It didn’t seem possible to pursue [the culinary program], it didn’t seem possible to go back [to teaching].”

She did end up deciding to stay in education, though.

“There was a lot I liked about teaching, and I ultimately decided that I wasn’t ready to give it up,” Jones said. “I was ready to be done with some of the stresses, but I wasn’t ready to give up the things I liked about the job.”

She said that her heart attack snapped her into a much more productive mindset.

“I had a reaction that was like, ‘I’m so thankful to be alive,’” Jones said. “Now, I have a perspective that’s much more balanced.

She says that makes her a better teacher.

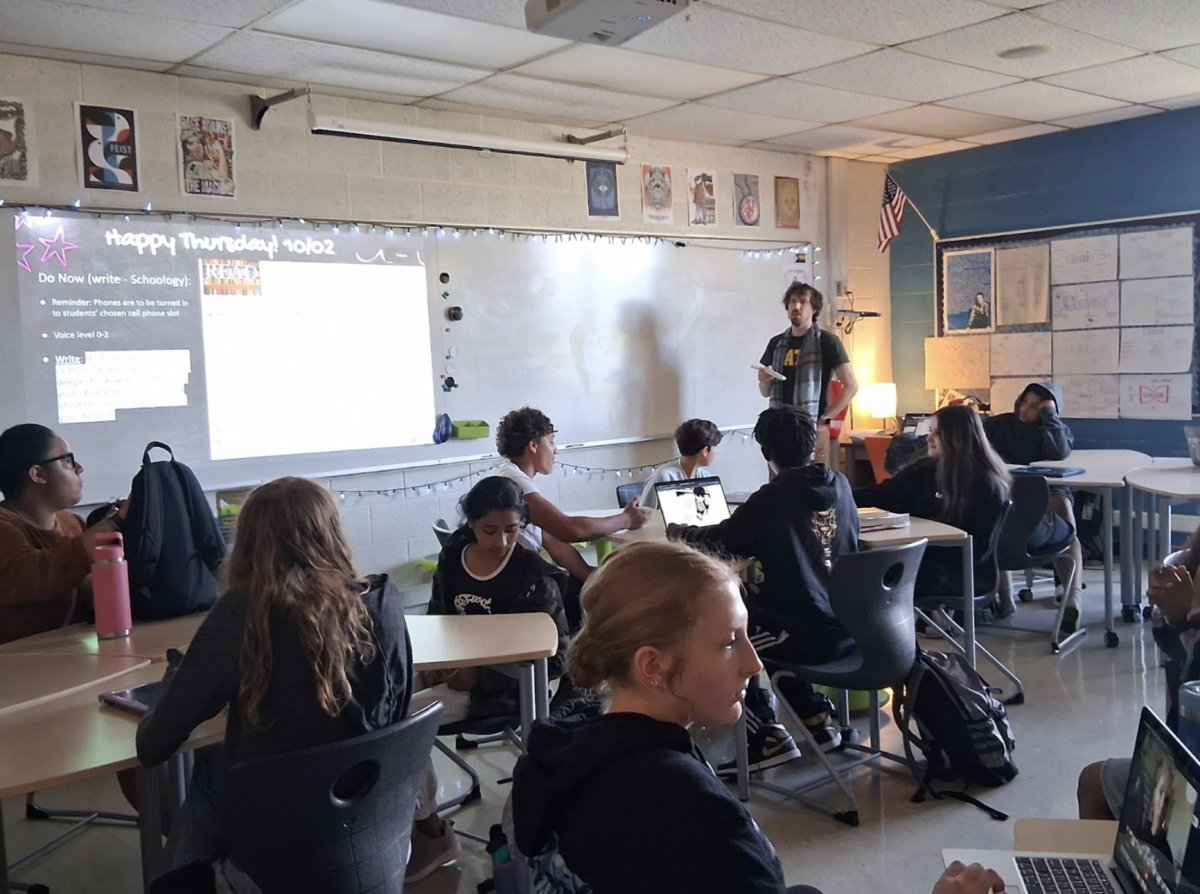

“We’re modeling for [students] all day long, so when we find our balance, that impacts the whole feel of the classroom,” Jones said. “When we’re balanced, we teach balance, and when we’re stressed, we teach stress.”

Jones feels like although things aren’t the easiest for teachers, the next generation shouldn’t throw that career option away.

“The degrees and opportunities in education are always waxing and waning,” she said. “For lots and lots of people, teaching is a fallback or a Plan C or D or E. Students always feel like, justifiably so sometimes, that it’s not a great financial decision. Nobody’s out there trying to live an underpaid life. Teaching is really a lot of fun. I hope [students] will not eliminate it from the life option list. It’s a great career in a million ways.”

Read installments one and two of this series at these links.