Your contribution will support the student journalists of Huron High School, help us to offer scholarships, cover our annual website hosting costs, and most importantly, allow us to keep recording history.

Healthcare access: the right to life

According to Dr. David Ansell, repeal and replace "really is a form of murder."

April 11, 2019

The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights declares “medical care and necessary social services” fundamental human rights. However, the U.S. provides only limited protection against financial harm to healthcare access.

For some, it means suffering until the next pay period to treat a sinus infection, knowing that insurance wouldn’t cover it otherwise.

For some families, it means sending kids with colds straight to the ER, where physicians can’t refuse care.

For others, it means living on the edge with the constant risk of heart failure, lacking proper medication to fight high blood pressure.

According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including…medical care and necessary social services.” In the United States, while healthcare is not guaranteed by the Constitution, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010 to broaden healthcare coverage.

The ACA essentially creates different pricing tiers of government-sponsored healthcare based off of income levels. It takes into account income as compared to the federal poverty level, with the intent to make affordable healthcare available to more people.

At Huron, aside from urgent care for immediate emergencies, most healthcare access lies outside of the school’s capacity. However, there are families that may not have access to healthcare.

“Typically, there are identifiers that we use at school,” said Waleed Samaha, one of Huron’s full-time social workers. “We also have conversations with parents. A lot of times it comes from parents, not directly from students.”

From there, he works with counselors, the school nurse, and outside agencies to come up with a plan to identify and access the proper resources.

The Ann Arbor Public School System has a partnership with the Regional Alliance for Health Services from the University of Michigan to provide health services. The Kellogg Eye Center, for example, has provided students with eye exams and glasses in the past.

“If you can’t see the material and it impacts your ability to function in school, that has an immediate impact on a student’s ability to learn and produce work,” Samaha said. When students are able to get a pair of glasses with the proper prescription, “they are able to function more successfully in school.”

Dr. David Ansell, Senior Vice President for Community Health Equity at Rush University, believes that wealth inequality is inevitable, but that healthcare inequity violates human rights. [T]he idea that someone should die early or so significantly earlier, simply because they don’t have healthcare or access to healthcare, is criminal. — Dr. David Ansell

“One, I think it’s one thing to have rich and poor people,” Ansell said. “Even the most egalitarian of societies are going to have people that are wealthier than others. Two, the idea that someone should die early or so significantly earlier, simply because they don’t have healthcare or access to healthcare, is criminal.”

In the United States, lack of healthcare access is primarily reflected by the cost of healthcare. For many, a single surgery or round of chemotherapy, or even insulin injections, can place a financial strain on individuals.

According to Dr. John Ayanian, Director of the University of Michigan’s Institute for Healthcare and Policy and Innovation (IHPI), the United States has a very high cost of care relative to other countries.

Ayanian, a member of the National Academy of Medicine, has advised Congress and other organizations in the country on major issues concerning health care. Now, he leads the IHPI, which conducts evidence-based research to evaluate healthcare policy-making.

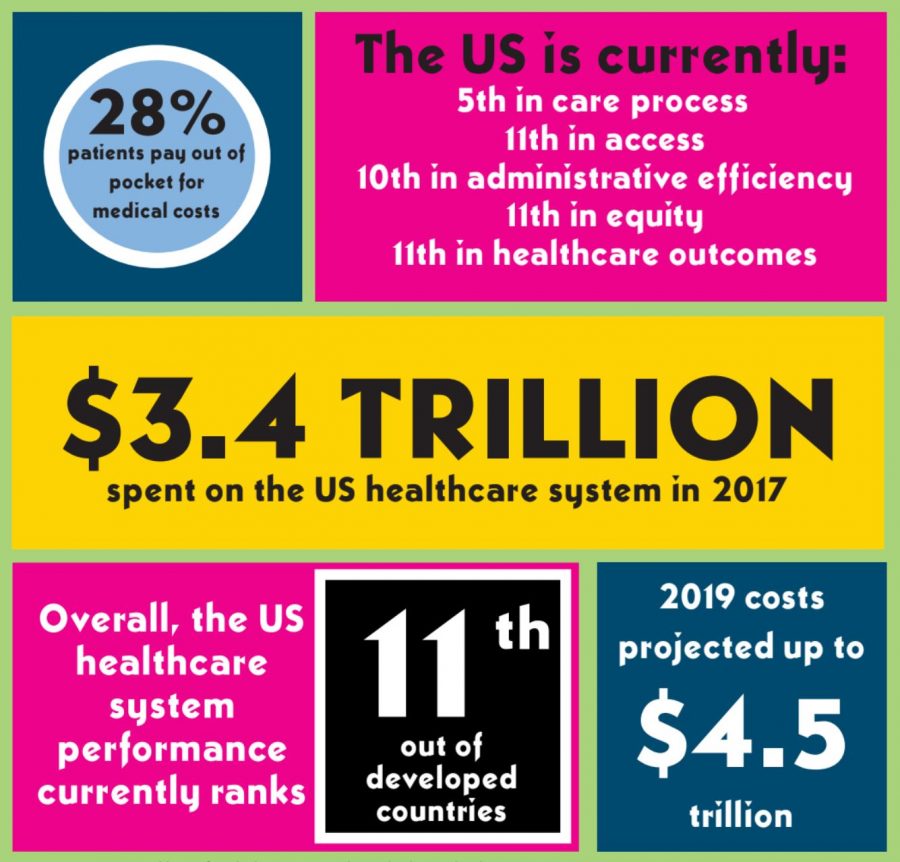

“We spend fifty to one hundred percent more per person on health care [than other developed countries such as Canada, Australia, and Japan], and we don’t achieve the best health outcomes for that added spending, whereas many [other] countries have longer life expectancies or lower levels of disability than we have in the United States.”

Based on data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the US consistently ranks the highest average cost for healthcare per person, averaging at $9,892.3.

Statistics from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development show that out of developed countries, the United States has the highest average cost for healthcare per person. Despite this, the U.S. lags behind in healthcare system performance. Dr. John Ayanian partially attributes this discrepancy to a lack of universal healthcare.

“Part of the reason is that, unlike other countries, we do not have universal health care,” Ayanian said.

Currently, there are three main types of “universal” or “socialized” healthcare systems. Single-payer systems in the United Kingdom and Sweden directly cover costs through taxes. There is a limit on how much is paid per person. Two-tiered or mixed coverage in France and Australia offers less comprehensive required government healthcare supplemented by private insurance. Some countries like Japan and the Netherlands have an insurance mandate, in which purchasing healthcare is legally required. Oftentimes, the government regulates private healthcare fees.

While these healthcare systems may meet the World Health Organization (WHO) definition for universal healthcare, the ACA still does not. In the U.S., there is limited protection against financial harm to access healthcare services.

However, Dr. Ayanian says implementing the ACA is the first step forward.

In Michigan, the ACA was recently expanded with the Healthy Michigan Plan, which provides healthcare access through Medicaid at affordable prices for qualifying low-income individuals and families. Research from the IHPI that surveys patients and providers concluded that the Healthy Michigan Plan has increased both the quantity and quality of healthcare provided in the state, particularly through its focus on primary care.

Ansell believes much more substantial change is needed.

“We have a big fight on our hands in this country,” he said. “Not only do we have to oppose ‘repeal and replace,’ we also need an improved ‘Medicare for all.’ So it can’t just be Medicare; Medicare does not limit your out-of-pocket expenses. It really needs to be no copays, no deductibles, elimination of pharmaceutical and insurance company profiteering – I would get rid of the insurance companies, and I would have it be publicly funded healthcare run privately. That’s what I would recommend.”

Beyond cost, Ansell explains that many other factors stand in the way of healthcare equity.

“Think about the social conditions of someone who doesn’t have enough money for food, and so half the month they go hungry, or they can only eat for really cheap (sugary drinks for example) and then their diabetes gets worse,” said Ansell, author of The Death Gap: How Inequality Kills and County: Life, Death and Politics at Chicago’s Public Hospital. “So hunger would be an example of a social determinant of health.”

Ansell argues that there are also structural determinants of health that may be manifested in the community where a person lives.

“There may be no access to grocery stores – it’s a food desert,” said Ansell, who sees citizens “assigned to neighborhoods of poverty” not only in Chicago where he works but also nationwide. “So you could have someone who lives in a food desert, with or without money, and they may not have access to food because of the structural conditions of their neighborhoods, or the economic conditions.”

Additionally, Ansell credits racism as one of the reasons healthcare lags behind in the United States “because there has never been a lot of appetite in this country for repairing the damage that slavery caused.” In a country “run by oligarchs” that tolerates “the demonization of poor people in poverty,” he sees a complete redistribution of wealth as crucial to fixing the system.

He uses an iceberg as an analogy: the unseen base of the iceberg represents the conditions where one lives.

“[T]he conditions under which you live have much more to do with your chance of living a long life than taking a pill [does],” Ansell said. “Let me give you an example of that, and this will show across the United States, it’ll show in Michigan, it’ll show in Chicago, heck it’ll show around the world: if you live in downtown Chicago, life expectancy is 85. If that were a country, it would be ranked 1st in the world. In fact, there are places downtown where the life expectancy is 90. But if you go literally seven stops on the L, the train line downtown, the life expectancy drops to under 65. That’s 25 years, and you can’t explain that by saying, ‘Well, people aren’t eating enough broccoli.’”

According to Ansell, there is toxic stress associated with poverty in poor neighborhoods that steals health away from poor people, contributing to high mortality rates.

“There are 1.5 million missing black men in the cities across the United States between the ages of 25 and 54, and if you say, ‘Where did they go?’, 900,000, almost one million, are prematurely dead, largely from heart disease and cancer, and 600,000 are in the criminal justice system. Just in our urban areas. Think about the implications of this.”

At the end of the day, the extent to which healthcare rights are human rights varies based on who you ask.

“I think by now most people in the medical field do believe that healthcare is a human right,” Ansell said. “I think people have begun to think it’s a human right. Increasingly, even across the population, people are beginning to agree it’s a human right. But we haven’t agreed as a nation; our public policies do not reflect these facts.”

As a whole, healthcare is a precarious subject, politically. As a result of public outcry, there has been some consensus surrounding the regulation of pharmaceutical prices.

“Since 2010, [it’s been] a very contentious decade in Washington related to health care,” Ayanian said. “In 2017, the Republican Congress came close – within one vote – to repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act.”

Ansell claims the current administration’s hopes to repeal and replace “really is a form of murder.”

“You know their policies are killing people, and the policies they would employ would kill people,” Ansell said. “Look at the map: many former confederate states, the slave-owning states and some parts of the west, did not expand healthcare to poor people. I think eventually they will because it’s way more costly to take care of someone when they have an extreme illness [as] opposed to when they are doing preventative care.”

In the United States, there has been substantial concern about rationing care with that type of analysis. But, in reality, we already ration care based on price and whether people have insurance coverage. — Dr. John Ayanian

In 2016, the average lifespan of an American dropped 1.5 years.

In 2017, the U.S. government spent 3.4 trillion dollars on its healthcare system. Yet millions of Americans lived without insurance coverage and healthcare. In 2019 it is projected that this cost will rise to 4.5 trillion dollars, without a corresponding increase in coverage.

“[Policymakers] oftentimes need both quantitative information from research studies and stories that bring those quantitative results to light, so sharing the experiences of individual patients or families that bring the research results to life is often very important work,” Ayanian said.

Ayanian sees a clear plan moving forward: incorporating public payers like Medicare and Medicaid, as well as private insurers; incorporating cost-effectiveness analysis, which determines treatment prices based on cost per year of life gained; maintaining incentives for innovative new treatments to be developed; and above all, making sure to help people.

“That’s affordable for society, and most other countries in the world use cost-effectiveness analysis to help guide the prices that they pay for new treatments,” Ayanian said. “In the United States, there has been substantial concern about rationing care with that type of analysis. But, in reality, we already ration care based on price and whether people have insurance coverage.”

Ayanian noted that getting the attention of elected officials and policymakers not only involves “health and financial data that might influence their policy decisions” but “helping them understand the human dimensions of the problem.”

“Fortunately, in our community, [healthcare access is] a relatively small [issue],” Samaha said. “It’s not a widespread issue, but even one [case] is too many.”