Life after incarceration

Removing barriers for non-violent prisoners to obtain work

April 11, 2019

When he was nine years old, Robert D. Boyd Jr., watched his grandfather stab his step-father to death. At eleven, he became involved in drug and gang activity. Boyd was deep in the so-called “thug life” when he was arrested and incarcerated.

Upon release, Boyd started working to turn his life around. But it wasn’t easy.

Prisoners are sentenced everyday, but most people forget what happens after felons have completed their sentence. Felon reentry, or return to society, is arguably the most important phase of a prison sentence due to the nature of reintroduction after an extended period of seclusion. Inmates can serve terms up to life — meaning an inmate could enter prison as a teenager and leave as an elder. Although felons may serve a duration that lasts long enough to change the scope of society around them, programs and organizations like the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) and The Streets Don’t Love You Back work to offer felons with job opportunities.

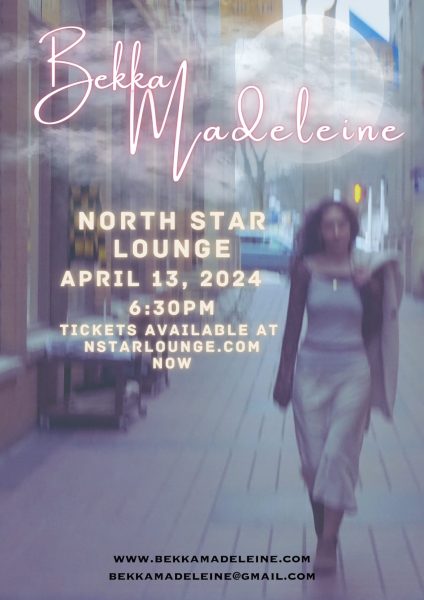

Robert started the The Streets Don’t Love You Back with his wife Belinda Boyd in hopes of educating against gangs, drugs, and violence. This foundation has affected thousands of people since 2009. It helps ex-criminals get back on their feet and find housing and employment. In 2013, the Streets Don’t Love You Back intervention program was started to help inmates find employment and housing and receive a second chance at life. The program is also incorporated in the court system, where kids can have felonies removed off of their records in order to have a second chance.

None of this would have been possible without the support of his mother, the inspiration who gave him the strength to turn his life to God and become a successful businessman.

“I think the government can fix the problem,” Boyd said. “[W]hen a lot of these people go out here and do their time, especially if you’re not a murderer, or messing with kids, or a sex offender…I think the government should give convicted non-violent felons a chance to work, a chance to have housing.”

Boyd explained that the checkbox asking if you have been a convicted felon on job applications should be removed.

“[W]hen they hire you for a job and they get your social security number, they’re going to do a background check on you anyway, so at least let that individual get a fair shot to go in, fill in their application,” Boyd said.

He also believes that all people should have a second chance at being able to live a functioning life to support their families.

“I think it should be a human right to be able to go out there and work and take care of yourself and take care of your family.”

Kyle Kaminski is the Offender Success Administrator at the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC), where his work encompasses offender education, offender programming in prisons, and reentry.

“What we are doing in prison with them is two major things: one is we are trying to do programming, evidence-based programming, that’s meant to reduce their risk when they return home,” Kaminski said. “So we’re trying to identify where their risks and needs are, and then trying to do programming to reduce the likelihood to use violence, or reduce the likelihood to use domestic violence, or, a lot of it is around, kind of, cognitive behavioral therapy, where we are trying to change where they think and react.”

Along with cognitive training and programming, the MDOC also provides inmates with a means of education. The state itself provides multiple programs to felons to either earn their GED or early college credit:

“The other major reentry piece we do while they’re prison is a lot around education,” Kaminski said. “We’re the largest GED provider in the state, so we run schools in all of our facilities. We also run vocational programming in many of our facilities, so men and women have the opportunity to get credentials in a vocational trade before they go back home. If they don’t have a GED when they come to us, they are likely to have a GED by the time they go back home, and we even have some college programming in some of our facilities.”

The MDOC’s system for felons works through different routes of programming. They decide the method of reentry on a case-by-case basis by evaluating the situations of particular felons.

“The types of services we provide, depending on what their needs are, would be things like housing (so we call it residential stability), we provide social supports, those can be basic things like bus passes or transportation, work clothes, basic toiletries, things like that, some of the things you need to live day to day,” Kaminski said. “We will provide additional job training, we’ll help them job placement.”

A clear example of an existing program is their residential stability process. Through this program, the MDOC provides returning felons with a period of free housing after they are released from their sentence, so that they have a chance to start a career without having poor living conditions or being homeless:

“Transitional housing generally is up to 90 days, so 3 months, we can extend that if there’s a reason to in the case, but we want to (as they’re approaching 3 months) we really want to kind of push them to say, ‘You’ve had 3 months to work and earn some pay, you should be able to get your own housing.’”

The MDOC’s progress has not gone unnoticed. Their success has recently been displayed in the past few years when assessing recidivism rates and success rates of felon reentry.

“The programs help,” Kaminski said. “So, we measure recidivism in a very specific way. For everybody who is released from prison, what percentage return to prison within 3 years? So, that doesn’t mean they got pulled over for speeding or they ended up in jail for a night because they were intoxicated, they must do something enough to return to prison in 3 years. Right now, our rate is 28.1%. If you go back 15 years, our rate was like 45.6%. About half of those people committed a new crime and returned to prison for it, the other half return for technical violations of their parole, so that’s another thing to look at, is trying to determine when it makes sense to return somebody to prison even though they didn’t break the law necessarily.”

The widespread goal of the state organization is to assist and supply felons with the means for self-sufficiency, and to change the lens society has towards felons. The MDOC believes that through persistent programming and decreased rates of recidivism, they can change how society thinks or perceives felons in the workspace.

Kaminski said MDOC’s goal for is to have folks come back out and for them to be successful and self-sufficient in the community.

“Trying to find a job as a felon today is as easy as it’s ever been, but it’s still difficult,” Kaminski said. “People are not able to secure good employment today because of something they did 10 or 15 years ago, where they did whatever the punishment was, whether it be prison or jail or probation, they did that, they completed it, and yet they are still being punished all these years later because of that criminal record. I think people are recognizing that that’s really not fair.”

Other countries have different standards when it comes to criminal records. In Hong Kong, a potential employer may not have access to a person’s criminal records with certain exceptions (like applying for a job in banking, then if the person has a finance-related crime, then they can get their application for finance license rejected.) Overall, records are permanent, but invisible to anybody but the Hong Kong Police Force and the person themself. For a minor crime (fine of less than $10000 or a sentence of less than three months,) the individual can get their record “spent” if they have not committed any additional offences in the three years after the initial offence. Criminal records can never be completely purged.

In New Zealand, people can get a lesser offence hi0-dden from the public if they have gone without an additional offence for seven years. Third parties are prohibited from obtaining an individual’s criminal record under any circumstance. However, an individual can provide their criminal record to a third party if they want to.

In Portugal, a third party is allowed to access someone’s criminal record with the consent of the individual. If an employer wants to access the individual’s criminal record, they must submit an application to see the individual’s criminal record in person. Depending on how severe a crime is, someone can get their record cleaned after a certain amount of years have passed as long as the person in question has not committed any subsequent crimes.

It is made harder for felons when getting out of jail to be accepted a job because of their criminal background. Many companies and businesses will be inclined to not hire someone if they are a felon. For example, to work at Amazon you must wait at least 7 years after being released from jail to be considered for a job.

However, Michigan has recently dropped the felony checkbox on job applications for NEOGOV, as of an executive order signed by Governor Rick Snyder in early Sept. of 2018. It is hoped that this action will influence other private businesses to consider removing that checkbox as well.